This conversation is about the album The Red Door: Clarinet Works of David Maslanka (2021)

Works discussed:

Three Pieces (1975)

Fourth Piece (1979)

Little Symphony (1989)

Eternal Garden (2009)

Trio No. 1 (1971/2012)

Trio No. 2 (1981)

A Litany for Courage and the Seasons (1988)

Matthew Maslanka: My name is Matthew Maslanka. I’m David Maslanka’s son. I’m being joined by Jeremy Reynolds who is professor of clarinet at University of Denver Lamont School of Music. And he has just released a two-CD set of basically everything dad ever wrote for chamber clarinet. And it is just a stunning piece of work. And I am grateful to be able to talk with you about it today.

Jeremy Reynolds: So thank you. Matthew, thank you so much. This has been a long time coming. And thank you for speaking with me. And anytime I can talk about your dad’s work and working with him and stuff. It’s always my pleasure. So it’s great. Fantastic.

MM: Why don’t you tell me a little bit about how this thing came to be?

JR: Yeah. So a very good friend of mine, Peggy Dees, who your dad also knew quite well. She was integral in getting Eternal Garden off the ground. She was I think the leader of the commission project. And she contacted – No, we met actually doing a recording session down in Florida for I think it was Carl Fischer. And we became really good friends and she roped me into the commissioning project for Eternal Garden and that’s kind of where things got kicked off.

And so of course, as a student I had played, several of the wind quintets, and in school, and of course, you know, the wind quintets are all the rage, and a couple of wind symphonies, as well. So I was really familiar with your dad’s work, but I wasn’t really familiar with the chamber stuff, as you said.

And so one thing led to another, and I was actually teaching at Northern Arizona University. At that time that I started just to sort of collect all this music, I reached out to your father, I may have even reached out to you I don’t know, that was back in 2000 –, maybe 2007-2008. So I don’t know if we started corresponding back then. But so I started collecting the music.

I actually ended up going back to perform at the Tucson Symphony for two years, and then ended up coming here to Denver, University of Denver. And, you know, the being a rather, you know, junior faculty member and learning all about academia and the tenure process. You know, I saw this as just like the ultimate tenure project, like, I’m gonna do this, and this is gonna get me tenure. And that’s like, I was very, like, you know, like, you know, like, just like tunnel vision, right.

Um, but honestly, I mean, it just, you know, I thought about I actually contacted Jerry Junkin, at one point at the Dallas Wind Symphony and asked if he would be interested in recording the first concerto and I think that was before he wrote the second one, I believe. And of course, I mean, I actually Jerry was at the time, he was really on board, but he told me what the budget was. And that just sort of blew my budget.

You know, I had I had $20,000 to do this project. And so that would have blown the project. So I scaled it back just a touch and ended up doing the seven pieces.

MM: You know, $20,000 sounds like a lot until you actually start doing things. And it goes real fast.

JR: Exactly. And you know, for the first CD – for the solo CD – we flew up to Missoula, we did a recital at the University of Montana. And then the next day, we actually worked with your dad on all of the solo material, all the solo Rep. And Heidi and myself, we flew up to Missoula, and we were up there for several days.

And then we recorded it that following – I think that was probably November or maybe even October – that went up to Missoula.

MM: This was in 2013?

JR: This was in 2013. Yeah, yeah. And then we recorded it in ’14. I think I’m almost certain Yeah. And then the next year, we flew your dad down to Denver, because it was a heck of a lot cheaper to fly him to here than to fly all four of us up to Missoula, which was, which is also really spectacular. He was actually in residency here for I think, maybe a week, week and a half, at the Lamont School of Music.

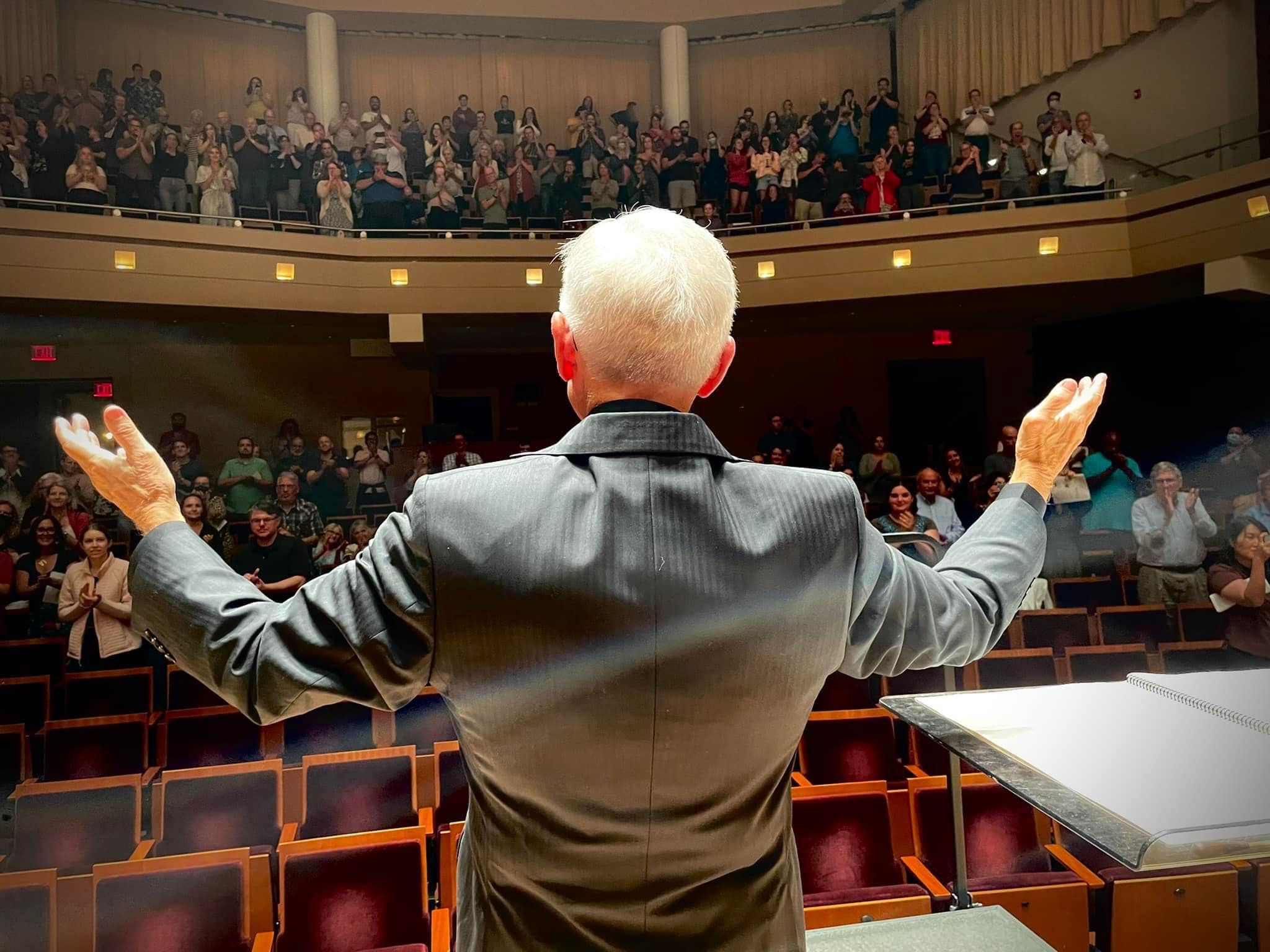

He worked – the wind ensemble did a piece or two of his, he did a couple of seminars with the composition students. And of course, he you know, coached us on on the trio music. And we did a recital, I planned the recital while he was here. And the one thing that I wanted to do, actually, and I never could, I didn’t really pursue it full enough. And I think the levels of the recording would have been so totally different.

But your dad actually spoke the words of Gringo before each movement, and he was on stage while we were performing. And we have a recording of it here in our archives, but felt the level of the recording would have been so weird. So I didn’t pursue it. But I just think it would be really neat to have his voice, you know, before each before each movement. We have it here for anyone who does, who does have access to our archives, the students and faculty So, so his voice will forever be in our, in our ears and in the halls of of the school, which is pretty cool.

But so, yeah, so that’s how that’s how it all started came about and how we ended up recording it. And, you know, I, we worked on it, we there was actually, It was interesting that your dad actually asked us to just record it, and go. Yeah. And I understand now why he wanted that. I really do. And it’s probably taken me, you know, at this point to really understand a lot of his approach and what he felt about his music and what he felt about – the energy of a room and how each performance can be very unique and very special unto itself.

And it’s I think, I imagine that, you know, he just wants– he wanted everyone to experience the music at that moment in time. Right. And so but I have to tell you, we did very little editing – we really did, we did very little editing, simply because of your dad’s use of the piano sustain pedal. Yeah. And that creates a lot of problems. A lot of problems with the intensity and the energy in the room.

So I actually we I did make sure in the in the recording in the liner notes that we indicated that very little was done – at your dad’s request, first of all, this is what he wanted. But I mean, I couldn’t go, you know, into into depth of why but I’ll tell you that darn sustained pedal in that piano. I mean, there were so many times where – well, no, not so many times – every once in a while we would have a take, that would just be even more special than the last one. I mean, really, you know, but that darn sustained pedal, it just it was it was amazing.

But I think because of that, what happened is that you really hear what your dad ultimately wanted, you know, and that’s kind of that’s kind of ironic, ironic about the whole thing, you know.

MM: The really interesting thing about doing whole movement takes or whole piece takes is that you are alive in the energy through the whole arc of the thing. And when you start chopping it up into little bits, then it’s easy to lose the power as you go forward.

JR: That’s exactly right. Yeah, that’s exactly right.

MM: And as I’m listening through the recordings, it’s so clear that you guys are absolutely focused. And it’s a, it’s a special thing, that doesn’t happen very often. And frankly, it’s clean as hell. Like – you guys are nailing this. So it’s not even like we have to edit around a bunch of sloppy playing. It’s you, you have put in the time to make those single takes work.

JR: We did I mean, first of all, I mean, I I have to give major kudos to Heidi and to Basil, and to Yumi, because they sunk their teeth into it. Yeah they did I mean, you know, I remember so vividly. And I don’t know if Yumi would remember this, but there was some stuff that your dad wanted, like that he wrote, and he was working with us and she said, “do you want it this way?” And he said, “well now, what do you want?” Like “how do you feel?” and I just remember just watching the whole thing.

I wish I had like a camera and a Polaroid of just the whole thing to watch it. You know and and, and, but what I think what you’re hearing is also what he did. I mean, it was really it was his inspiration. It was his, it was his working with us – it was his challenging us and he really did.

Because he sat there, and he would not tell Yumi exactly what to do. And it wasn’t that he was being stubborn. It was just he really wanted. I mean, again, I mean, I hope I’m not speaking out of turn or, or trying to read too much into stuff. But I really felt that he was really asking her to find out or to figure out what the music meant to her, and how did she want to play it? And how did she want to put her voice in, in conjunction with what he wrote, and the inspiration and stuff like that.

So, I mean, it really I have to say, I mean, I’ve had, you know, this will definitely be in the top five, if not the top experiences of my career. I mean, seriously, it was, it’s something that I I’m very proud of. It was it was amazing to work with your dad, it was also a treat.

At that time, as a student, the infamous David Maslanka – the music and the man and, and all this stuff that all us wind players, just wanted to sink our teeth in. And so, you know, I mean, even though I was here, and getting more and more established in my career, I still saw him as like this composer that was almost unreachable.

Yeah I remember as a student, so that was also a deep thrill to be in the same room as him. And he really, he really meant a lot to me and, really to all four of us. I know, Heidi, there was a time that he came back to Colorado a couple years later. I wasn’t able to get to Boulder, but Heidi drove up and they sat next to each other and they had dinner afterwards.

He came over to Madrid. I actually have a picture that I in my phone I was trying to find for you that I can send to you. But he came over to Madrid to hear us play the Three Pieces and the Fourth Piece. I actually think it was more inspired because I think your mom wanted to ride horses on a Portuguese beach.

MM: Yes she did.

JR: Yeah, so they did that on that trip, I believe whatever, a special kind of horse is indigenous to Portugal. So I think they made like a double trip out of it. It was really awesome. And I think – I really hope – our intent – is that we are performing, basically from his mouth, into your ears. Approach into, our world now, and, forever hopefully. Into his into his mind into his world into his.

The trios are – I don’t know anyone who knows the trios. Honestly, I really don’t. I don’t know if it’s because they are so terribly difficult. Or I’m not really sure, but not a lot of folks know the trios.

MM: So one of the interesting things about the trios: not only are they from a period that nobody really gets into, but they’re also for a more – it’s not an obscure group of instruments, but – you know. The music itself is just sublime, though.

JR: Yeah, it’s really wild. And I think you’re absolutely correct. And – correct me if I’m wrong – but even in the solo CD, even the Three Pieces, and the Three Pieces are also from a time where we’re not really familiar with and, and I think that’s the time he lived in New York. Is that correct? Before you moved to Montana?

MM: Yeah, we moved out to Montana in 1990. Yeah, so most of this music was written before then. Everything but Eternal Garden is a New York work. I actually wanted to maybe get into a little bit of the music. I was struck by – so, a lot of the music from this time is characterized by extreme violence. It’s very, very loud, very angular, the music that is – he’s frustrated with a lot of how his life was going and his inability to be himself effectively.

And you really get a sense of him, kind of banging on the edges of maybe the universe and the boxes that he was in using the materials that he was able to use. I wanted to start off with the second movement of the Three Pieces a little bit.

JR: I knew you were gonna play that.

MM: Yeah, I mean, hey, it’s so – So you’re really going for it!

JR: We really went for it. And it’s – yeah, we went for it. And I, Matthew, I have to tell you one of the other little anecdotes is that when we were working with your dad in Missoula, he just kept on saying, “louder, louder, louder, louder, louder.” And when it was, he was so dialed in. Like you said, it was almost as if he was reliving that moment, you know? And you could see it in his face, and you could feel it in his energy.

And most people who have worked with him would probably say he’s a relatively quiet guy. But, but that almost that silence and the experience in that room that we were in at the university campus was, that was almost deafening as well. And you could you could feel the energy and like you said, you could feel the frustration. He was so dialed in that the second he felt either one of us letting up, he said, “more, more, more.” I mean, he was he was relentless.

And I was so physically tired that we ended up taking a late flight to Missoula. And I remember Heidi and I, we had a glass of wine. That’s all we did. We had a glass of wine, we toasted the whole experience. And I remember sitting in the airplane seat, I don’t remember buckling, the seat belts. And Heidi had to physically wake me up when we got to the gate. That’s how physically tired I was – because just go, go, go, go, go.

When I was listening back initially, many years ago, I was thinking that, does it really capture the essence of what he wanted? And I, I think it does. I think it’s one of those things that you also have to see my head turning bright red in a concert to also experience it, but um, yeah, but we really went for it. And hopefully the intensity is really what comes across that we just do not let up.

So that is, I think, the hallmark of dad’s writing is the relentless character that you’re talking about. And whether it’s relentlessly loud or relentlessly soft, there’s something that he’s trying to get to, trying to push you to your limit, and then a little bit further, so that there is nothing else in the universe except this sound and this moment.

In Eternal Garden in the fourth movement, I think he probably added a good two, three, maybe even four minutes. Just hold – like you said – there’s one movement where I’m just playing so quiet, and reverse. It was absolutely reverse. In that room, if he heard me at all give a little bit extra or a little crescendo – “No! Less, less, less, less.” And the fermatas, I mean, it’s just –

Jason Shafer of the Colorado Symphony, he called me up when it was released and said, had a lot of really nice things to say. And, and he commented on how much longer the last movement is, and we started talking about it. And I said, the fermatas, especially, we held it – for that reason. Not to take away from the Three Pieces what you wanted to do you wanted to talk about, but, reverse it’s the exact same thing.

MM: Yeah. I’m gonna play a little bit of Eternal Garden in a minute. But that idea of “we’re going to hold this a crazy long time because the sound needs to settle in the room.” The sound needs to be right. You need to be in that place. It’s not there yet. It’s not there yet. It’s still not there. Now, there it is. Okay, there it is. Okay, fine.

JR: It really – yeah, I’ve never experienced anything like that in my entire career. Every once in a while, “can this be played quieter,” or whatever. Not for that extended period of time.

MM: Part of the amazing thing about his writing is that it supports that level of drawn-out-ness. It coheres. And that’s due to a faith in your ability to be present.

JR: Yeah, exactly. Yeah. Absolutely.

MM: I wanted to play – actually – the next movement of Three Pieces just to get a sense of – so there’s the violence in the early music, but there’s also an intuition of tonal harmony. It’s an intuition of the like, there’s the roots, where he found music interesting. Oh, caught it right too soon.

JR: Because it gets even more beautiful. I know. It’s simple, but yet, it’s so good. Yeah, it’s so gorgeous.

MM: So the really interesting thing for me is you need the same focus to play that as you do with all the nonsense you’ve had to do for the previous movement. Like, block chords themselves are some of the hardest things to do.

JR: Yes. And we had a discussion actually. So my colleague, Warren Deck, who used to play in New York Philharmonic, he’s the Tuba Professor and he was in the back, and we had a nice long discussion about intonation in the section. And I think it’s really important to know that to make sure I played in tune, and really go for it. I did do what maybe some folks would consider a tad unconventional for some fingerings, not that we have a lot of options.

But whenever I could add keys or open up tone holes to get the pitch so I could really go for it, because the clarinet tends to go flat when you really go. I did everything I could on my power to do that. And then Heidi and I actually did spend a good couple of sessions just practicing our releases. So we could really work on sustaining. I also could work with her to get the kind of the shape of the piano and how the piano sounds sometimes dissipate, and stuff like that. That’s the kind of work we had to do for that section.

MM: So, when you’re talking about releases, they are deeply undervalued, I find. That is the difference between a good and a great ensemble work – that you’re stopping together. It’s hard.

JR: You’re absolutely right. It’s so hard. This whole project and this whole preparation and stuff, it will be one of the top experiences of my entire career, and it probably will be for my entire life, because it really stretched me in every capacity as a musician, as a clarinetist – technique along with the musicianship, control the instrument, all that stuff. You hit the nail right on the head.

MM: So, the Three Pieces, ends with this… it’s a question mark of an ending. It ends with this beautiful sonority. And then the Fourth Piece takes up right where that left off and goes, “we didn’t answer that.” And we need to open this case back up and see what’s going on. So, you get the the block chords that we end with, that we then start with.

But it’s this sense that there’s something here that we need to figure out. And one of the things that I find, maybe, at the core of his music often is going to this hard place. No, there’s more there. No, there’s still more there. We’re going to take the time and see what’s actually going on. In his early music, it’s a lot about going into places of rage, and trying to process. And the later music, it’s about going into places of peace and letting those open up. When we start in Eternal Garden, it’s a lot of the same dissonance that you find in the early music.

JR: Yeah, absolutely. Which I hadn’t heard in that way without the juxtaposition of the earlier music.

MM: And it’s as though he’s going back to the early music and saying, It’s okay. It’s okay now.

JR: I hadn’t thought about the chronological in advance. And it was actually all the records that wanted it in order. I don’t know, maybe you and I talked about it, too. I can’t remember. But I hadn’t thought about putting them in order. But I’m glad we did, because you can hear the development. You can hear his lifespan, you know.

MM: I often describe his musical output as one long meditation. How to be a person. How to be a creative person. How to open yourself up to the universe.

JR: Yeah, that’s great. There are a couple of really cool effects that show up in different places. When I was listening through this time, we got to the second movement of Eternal Garden, which is “On Chestnut Hill”, and I just started, the tears came. Yeah, it’s one of my very favorite things. It’s also a callback to his earlier piece, A Litany for St. Francis in The Seasons. [A Litany for Courage and the Seasons (1988)] I wanted to just play a little bit of that.

So this is also music from this time, it’s the late 80s. And there’s an incorporation of the previous music in a new context, something that they worked with a lot. So how did that come through in your performance?

JR: Those are some of the moments where I really just enjoyed it. I enjoyed playing it, I enjoyed sinking my teeth into it. I don’t know if I would say I went that deep in moments like that.

MM: I feel like I’ve gone into more of an analytical thing as maybe a defense mechanism, in some ways. For my whole life, I’ve been immersed with this music. And a lot of my own journey as a person has been about coming into real contact with my heart center with my emotional truth. I always knew that this stuff was there. But engaging with it on structural levels or on research or analytical levels was an easier way to integrate it, to approach it.

JR: That makes sense. So at this point, I have the richness of the connections that happen with the music. And I am, I find, more easily opened to it now, which is a great blessing. But that will open up a lot of feelings. You know? It will. I’m even tearing up right now just even listening to it thinking back. No, seriously. Not to be overly dramatic, but it’s true. I know your father in a much different way than you do.

This was a project that I was – Everybody knew at the time that I was doing this project, because it just meant so much to me. I have a friend here who I went to the school in Cincinnati with, he’s a bassoon player turned urban planner. He’s brilliant. He’s absolutely brilliant. And he has served at some capacity on the board of the college symphony. And he helped me write the grant, because I had to get the grant.

Everything about this project was, “I have to do it, I have to do it, I have to do it.” If there was anything that was getting in my way to stop me from doing this project, it would shatter my month or my year or my day or whatever. It’s part of my life now. There’s a couple reasons why it took so long for me to get this project out.

Part of it is that I am a cancer survivor. And almost three years ago, I was diagnosed with non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Every time I came around to work on the project, it was like something almost got in the way. Everything was fine with it, my treatment, everything’s good, you know. I’m two years out, which is great.

First of all, it was awesome to go back into this music last summer, and to start putting the finishing touches, during COVID. It was awesome. It was like a beacon of light, if you will. It was always like this bright shining energy that was always a pleasure to come back to and it was great to listen to it over and over and over. And it was never old, it was never stale. It was always refreshing.

It kind of hit me that I do kind of wonder if your father knew that the music needed to be released and into the world at this time. I really do. I went through all my garbage, unfortunately, you know, after he passed away. So I didn’t have the opportunity to share this information with him or these experiences, which I think I would have, to get his insight and stuff like that.

I told Heidi this several times when we would talk about it. And I would ask her opinion about stuff. We had a really deep conversation about it, that we really, I really wonder if David knew that we were going to go through this crazy time in our history the past 14 months. And we would just need something exciting and awesome to sort of, for us musicians to really latch on to. I really do mean that. I really do.

MM: So for a long time, he’s discussed this in a number of places, the idea of coming to a time of crisis. Now, he could see the signs as well as anyone that everything is accelerating. And so things are gonna start to break down, things are gonna start to get crazy and chaotic and weird and difficult.

In one of his last public appearances, he talks about, during times of crisis, you can either fight or you can sing, and we choose to sing. And what making music does is that it connects us in a way that no other power can, I think. There’s the people on stage making music together. There’s the people in the audience listening to the music. It is impossible to hate while making music. And so regardless of the chaos, regardless of the mess, what we can do is make this part of the world beautiful.

JR: Yeah. And that’s how I feel about the music coming out at this time. Honestly, I really do. You know, I really do.

MM: So it’s an important thing that you’ve done here. And I really wanted to thank you for it.

JR: Oh, thank you. I appreciate that. Yeah, I do.

MM: So it’s not just the music. Coming to grips with him personally and to the music in the way that you have is something that very few people have had the opportunity, or the courage to attempt. And it’s a great gift that you’ve given us.

JR: Don’t make me tear up. I appreciate it. But honestly, the gift was ours. It really was – the gift was ours. The gift was to experience this and to go through the journey. When I started thinking about this, I just became so obsessed. I had to do it. I had to do it. Other than like, trying to survive as a musician. Make sure I’ll have a decent retirement or whatever. Put food on the table. I think there’s been very few things that I’ve been so unbelievably obsessed with. It was amazing to sink the sink the teeth into. I was equally inspired, you know, equally inspired by Heidi, Yumi, and Basil.

When we were doing the trios, the movement with the trio, the one with Basil when she has to strum inside the piano.

MM: So I wanted to talk about that, because there’s a few places where this autoharp thing comes in. There is in Eternal Garden, and then also in Images as well as the Trio. And it’s a timbre that I just forgot existed and how prevalent it was. And it’s just a cool thing. I’ll just play a little bit here.

And there’s this sense of, “we want to do tonality, but we can’t do straight tonality,” especially at this earlier music. We’ve got to do something weird with it.

JR: And you know, I have to share a little funny anecdote. I don’t think I ever told Heidi this ever. I don’t think ever. But in preparing for it to try to get the sound that she wanted. You know, she worked all sorts of different, you know, pencils, or erasers or whatever she wanted. And we had it set, like she had it set. And on the day of the recording, she comes in with more things. I just wanted to say, “Heidi, we already figured this out. You’re going to drive me bonkers.”

But again, Matthew, I have to keep on coming back and saying, like, that’s how everyone was. It wasn’t a matter of like wanting to get it right. Even to the bitter end, we wanted to try to really make sure we captured the essence of the music. I don’t think I ever told her this. And I probably should tell her this before this gets aired. I think back and I just thought to myself, “Oh my god, oh my god. Oh my god, what is she doing to me?”

MM: Speaking of Heidi, I wanted to play a little bit from the first Trio. Just the kind of virtuosity that she’s able to bring to the table here.

JR: And the chord? You cut off right before this amazing chord! Like, after all that, and all of a sudden, it’s like… Alright, here we go.

MM: Yeah, it’s just this delicacy of touch that she has. And the ability to get from very, very loud to very soft, and to carry that line through.

JR: And I have never collaborated with anyone that is able to play so loud. And that’s another item that … only I will experience that. Because when we play this, I really stood more in the crook of the piano to get a nice sound. I will be one of the very few people, and actually your dad too, because of the times when he sat on stage with us. She just sometimes plays so loud. I admire that with any musician.

There’s an amazing clarinet player, Håkan Rosengren. He teaches at Cal State Fullerton. And he reminds me of the same thing too. Some of these recitals I’ve attended of his have the same energy, the same spirit, the same control & mastery of the instrument. I was very lucky. Heidi and I have been playing together. Well she played for my interview here. And we’ve been inseparable ever since, which has been really cool.

MM: I wanted to play a little bit of the fourth movement, to get a taste of the violin, with the lyricism that Yumi brings here. Just beautiful stuff.

JR: Yeah, it is.

MM: There’s a liquid lushness to her sound. All the way through. The second trio – there’s this bit where you yell in the middle of the thing.

JR: And you know, I never asked your father this, but I want to ask you this. Where did that come from?

MM: Yeah, I don’t know. But my immediate reaction was both as a wake up for the audience to say, “Look, I know this is like the 15th piece in this new music recital. Just wake up!”

JR: Yeah. And then after that, Heidi actually has to sing along. It’s such a great texture. I don’t think honestly, it would have worked with a male voice. It creates an etheral sound. And then the viola sound as well.

MM: The whole thing works beautifully. Just a hell of a thing.

JR: And then while Basil is doing his thing, Heidi puts golf tees into the strings, which you can hear. It’s only like a very specific range. It doesn’t sound like a toy piano, but you have to listen really closely. That particular range of the piano is surrounded by other stuff like Heidi banging on the piano. It’s right in this very specific spot

MM: It’s worth listening along with the score.

JR: Yes, absolutely.

MM: Not only is the viola sound this gorgeous thing, like Basil is just just knocking it out of the park, but the chamber work between you guys – the handoff between the notes is so effortless and smooth. It’s just a pleasure to hear.

JR: Thank you, really appreciate it.

MM: Also very hard. It’s the kind of hard that results in a thing that sounds effortless, which is the best sort of thing. Like the swan is gliding along while madly paddling beneath the surface. And then we get into Images. And again, the autoharp.

So this is 1987. So this is right toward the the realization of, “I need to go to Montana, because that’s where things…” And you can hear him opening up. And the music becomes more spare and more serene. If you look in the beginning of the third movement here, he starts to strip down. And this is the starting point, I think, of the transition into the more simple music that he writes, going forward from this point.

This prefigures a lot of the music that he writes in the 90s with the kind of tonality and the pared back open harmonies. I didn’t know it went back this far. You always have to go back to go forward in some way. He changes the character, so beautifully in there. Just a gorgeous thing.

JR: Gringo is – it’s an unbelievable piece. Really is. The sounds. What’s the one where it’s just Yumi? This movement for me has a lot of angst. It gets higher and higher. And that wailing sound. I don’t know what it is. It also looks very uncomfortable. And I also wonder if that also helps the music. As a clarinet player, I can imagine playing like this so high up, and just like physically, it looks awful.

MM: That’s the ticket – the discomfort. It means you have to lean into it and commit into it. So there’s a personal parallel here. So this piece is written in 1987. My sister was born in 1985. In the ninth [11th] movement here is a song Mom sang to us as kids.

JR: Seriously? Yeah. I did not know that. Interesting.

MM: Go to sleep. Rest your head. Go to sleep, my little baby.

JR: He never told us that.

MM: And you find the songs that Mom sang sprinkled all the way through his music. Seriously? Yeah. So, in the euphonium concerto that he wrote for me, there’s a movement called The Water is Wide. And it’s the spiritual, but it’s the way mom sang it. Because she makes it 5/4 in a couple of places because she wanted to hold it out.

For Dad, I think, my mom Alison was the grounding. His link to the Earth, his link to reality in a lot of ways. Like he lived in the clouds and she lived in the world. And there’s a deep rootedness to these songs that he found especially captivating.

JR: Amazing. This has been just an absolute pleasure to experience. Thank you. It was an absolute pleasure and will continue to be. Our wind ensemble director actually asked if I would play the second concerto next year.

MM: Oh, fantastic.

JR: It was a real gift. I haven’t spoken to Peggy Dees in a while, but I’ll probably give her a buzz in a couple of days, and again thank her for involving me in the Eternal Garden commission that sort of kicked off the whole thing. It’s been such a real pleasure, and I will always remember it with a lot of fond memories.

MM: Well, you have a monument of passion here.

JR: Maybe a little crazy sometimes, too.

MM: What interesting thing ever got done by normal people?

JR: That’s exactly right. It’s been lovely to talk with you. You too. Yeah, this is great. I’m so glad. This is a great idea. It’s been great to relive it again. I love talking about my experience in this music and any opportunity to share. I love it. I can’t get enough of it. It’s like the finest of wines or the finest of anything. It’s just great. It’s just awesome. There’s always more there, the more you look at it. Absolutely. And that’s why I was saying before.

When I finally last summer said, “Okay, I really want this to get out into the world.” Coming back to it, listening to it, I feel like I heard new things. I feel like I experienced slightly different feelings or slightly different emotions. Truly! It was really spectacular. It’s timeless. It’s really great.

MM: Where can people find you online?

JR: Folks can find me on the University of Denver Lamont School of Music website. folks can email me through the university. That’s just fine if they want to reach out. Absolutely. I have a couple other recordings as well on YouTube as well if they’re interested in some other stuff. One thing was that I premiered some stuff for viola and clarinet that was written for us. Kenji Bunch and Libby Larsen wrote some stuff for us. And so that was another reason why this got a little delayed too. I think the best way to contact is through the University website.

MM: Thank you again. I’m excited to be to have this in the world.

JR: Me too. Thank you so much, Matthew. Really appreciate it.

Jeremy Reynolds may be contacted through the University of Denver.

Other Reynolds albums:

American Voices: New Music for Clarinet, Viola and Piano (world premiere recording)

Libby Larsen • Kenji Bunch • Dana Wilson • Michael Kimber • Anthony ConstantinoSpring Fantasy: Trios for Clarinet, Cello and Piano

Robert Muczynski • Carl Frühling • Nino Rota • Pavle Merkù