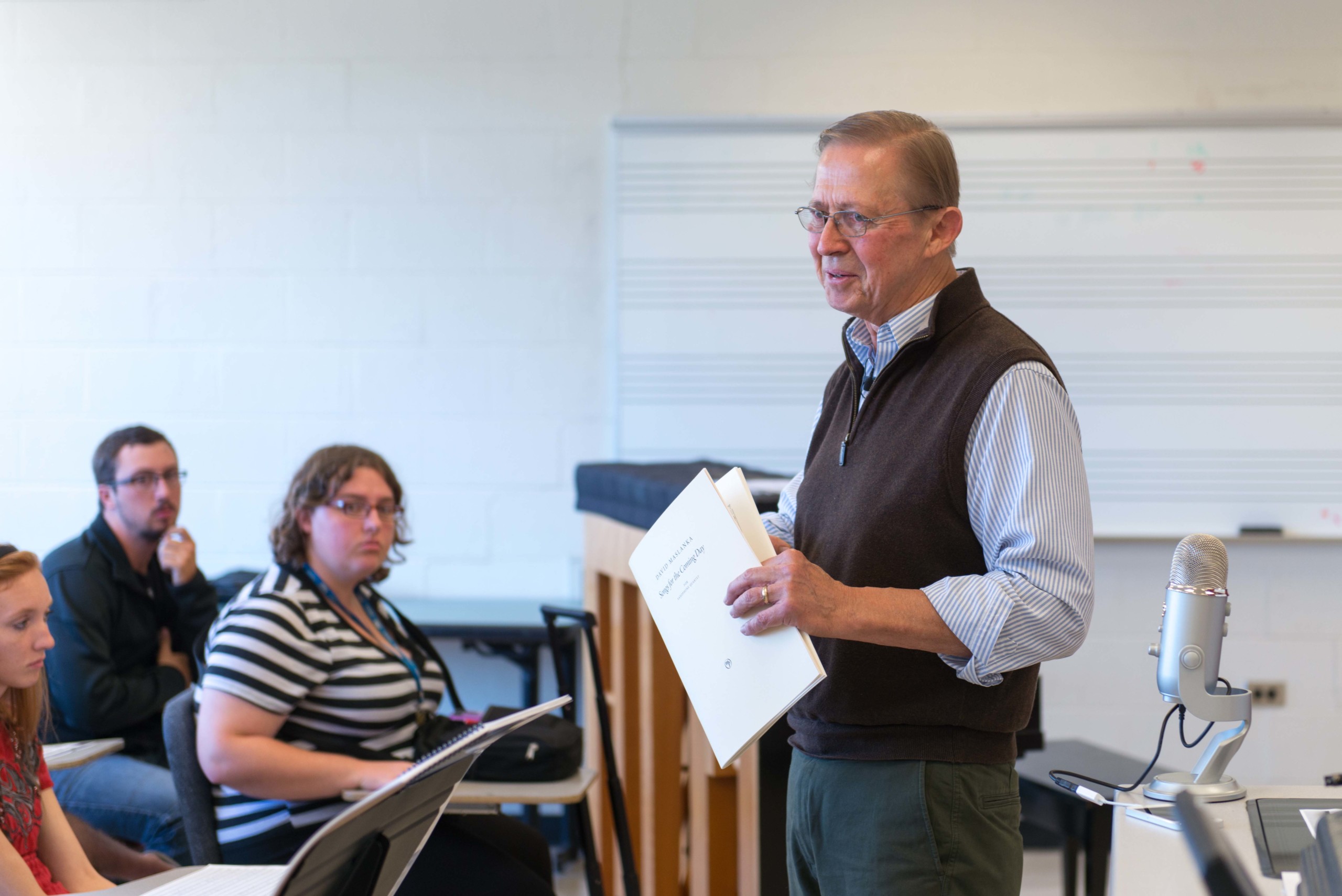

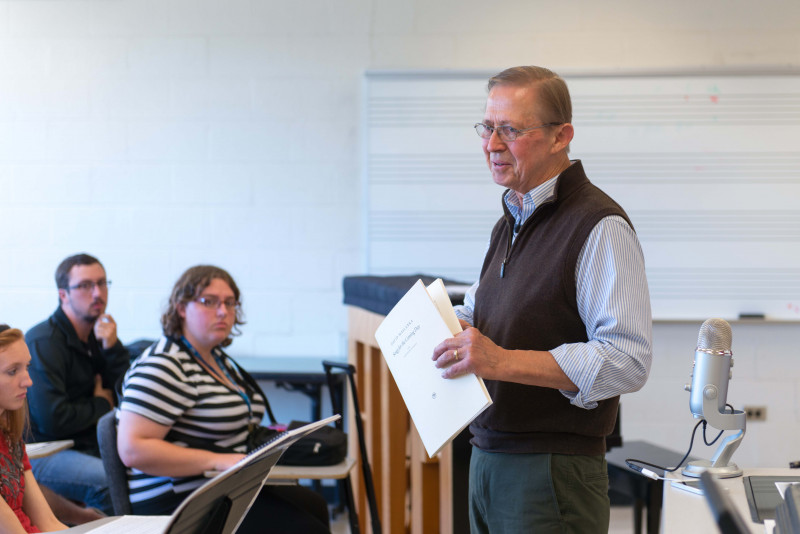

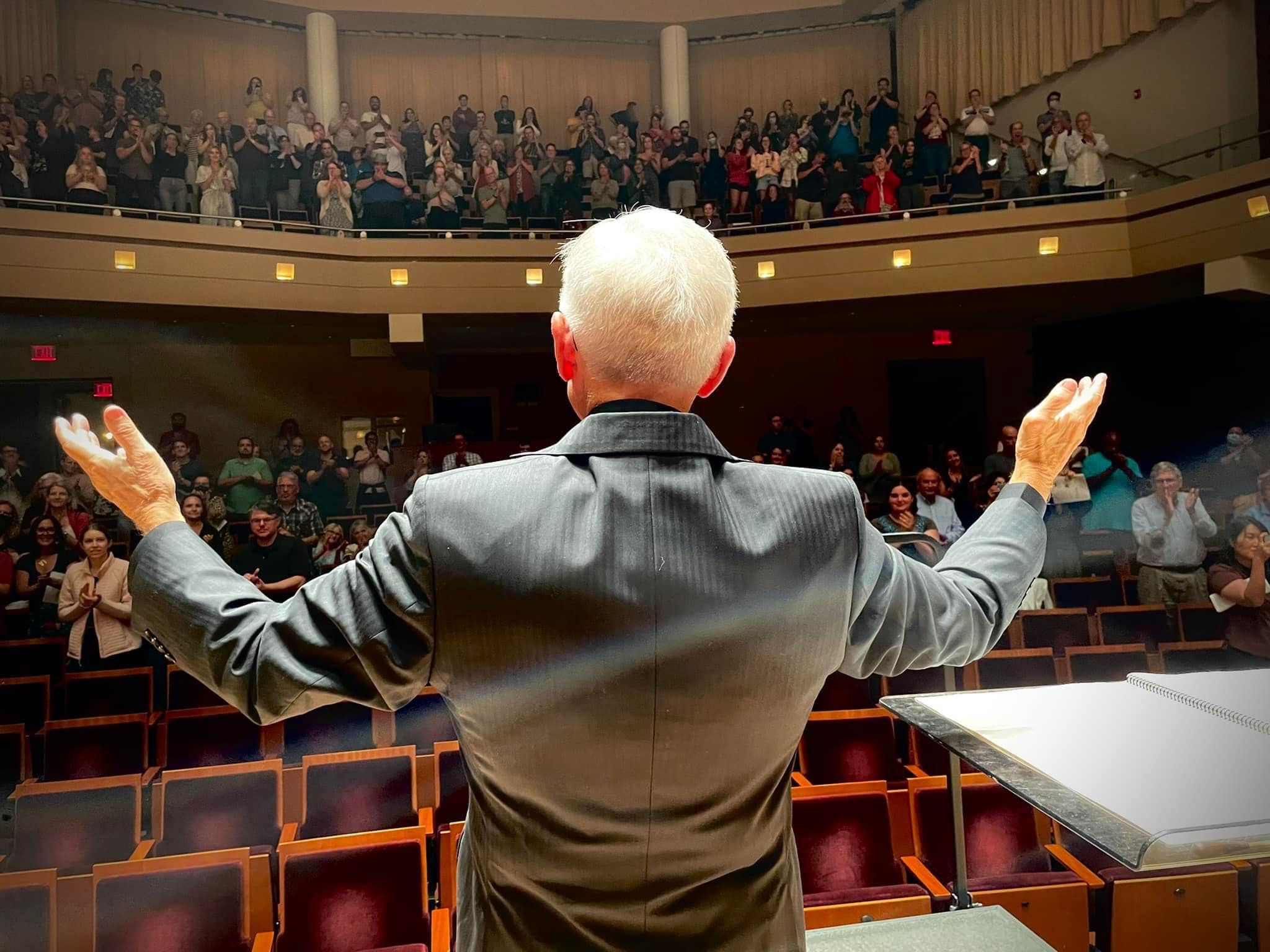

In October 2016, I (Matthew Maslanka) accompanied my father to Middle Tennessee State University where I photographed and recorded his masterclasses and rehearsals. This is his first masterclass, on October 24. He helped produce his final CD during this visit.

Audio Recording (1:05:22)

(transcript below)

David Maslanka

Thanks for that. Thanks for for being here.

I wanted to tell you a little bit about composing and to show you some things concerning Bach chorales. This has been a foundational thing for me for a long time.

A huge amount of things have happened in the 20th century and in our own time. The options that you have for technical things in music are extraordinary. You have to kind of not look at certain things in order to be able to focus on something that you might really want to do. And it might seem like a complete backward kind of motion to take something like the Bach chorales and make them a center of the life. And I’ll just tell you a bit about that.

I’ve written a lot of music. Now there’s something about I think about 150 opus numbers at this point, and still very alive and very much interested in writing.

But composing makes me nervous. And does that make any sense? Composing makes me nervous. Because I don’t know what’s going to happen. And I don’t know what’s supposed to happen. Right? I don’t start I can’t start with a pre plan of any kind. I simply have to open and trust that the thing that wants to happen is going to come through.

But I discovered and really began to be conscious of the fact that I was nervous about beginning my composing, oh, when I first moved to Montana, and that was now 1990, 26 years ago. And so what to do about it? I took first Bach keyboard music and simply began to play a bit. And then I found my old chorale book from freshman theory. And I took it out and I started to play and to sing chorales. I’d play all the parts of singing soprano, then sing alto, then sing tenor, then sing bass.

And I would do this until I felt better. Simple as that until I began to feel subtle, and that I can make that transition internal transition intomy own composing. And I persisted in doing that over all these years. And at this point, I have gone through the entire 371 chorales singing all the parts, maybe 25 times. So when I finished the book, I got to the beginning and I started again and and start singing again.

So the relationship with each of these chorales has become deeper and deeper and deeper and deeper. And there is a very definite kind of personal character. I’m not analyzing these things. That’s not what it’s about. It is being directly present with the moment of music as it is happening in my voice, and is happening through my hands.

And then, over the course of time, I began composing chorales in this old style, just for the heck of it. And to date, I’ve composed maybe 250 of these chorales. Take a melody out of the book that appeals to me at that moment, make my own composition of taking the original soprano, making my own alto, my own tenor, my own bass. And I do this by singing is not an analytical process. It’s a composition process. And so I’m making small compositions in the old style.

So this practice has radically changed how I compose music. I’m not composing music in the old style. I’m composing music now for me here, but it is informed by a very deep understanding of the old language. So the old language now has a chance to move forward through me in this new way.

So I wanted to start by showing you some of this process. And so I’ve got some pages here, and I’m going to let you pass them around and see so they printed both sides. Take some and pass them back. Someone passed back.

You have enough? Okay. Okay.

Yeah, I want you to sing with me. So we’re going to do some singing together.

The one I want you to look at, well, first off, this is a the printed page, here is a copy from the book that I use. And you see that I have simply kept track of the dates, that I’ve sung these pieces. So the earliest date, you’ll see at the top of the page is 1992. So that’s why my first time I actually put the date down on the page.

And it just got to be a thing that I just couldn’t keep track of the day. So I have this kind of history of what I’ve done. I’ve sung these pieces that many times. And I’d like you to look at number 321.

And I don’t have much of a connection with the Christian tradition of these things. But I have simply interested in the music because the melodies are old chorale melodies. But these are ancient melodies, most of them, things which have come up in the same way that folk music happens. They’ve been sung by generations of people until a shape emerges, which is very satisfying. And these shapes are almost always extremely simple. I’d like you to simply look at melody here for number 321.

(plays melody on piano) And so on.

That’s about as radically simple as you can get. And it comes under the heading of what I say for myself of what I would call a dumb idea. That is, it’s so simple, that if you had it as a composer, you’d say, I don’t think so. Because that’s been done. And it’s been done, and it’s been done. And it’s been done. I mean, it’s a few notes out of out of a out of a scale. And that’s it. That’s your tune. And yet, when you finally move through all of this, the power of it begins to emerge on its own. So I’m going to start with you. I’m going to play all parts and I want us to sing soprano lines. See, see how that feels.

So find your voices, and let’s see what happens to you. (David, class sings soprano of chorale)

Okay, all right beauty and power in that in that music. Okay, find the alto line now. If, men, if you can get your voices up there. (sings)

If you’re not then sing the octave lower.

But the men – let me hear you. Can you sing the D? No, about F sharp? Okay, that’s about as far as you have to go for for male voices. Well, the end of it gets a little hairy. But let’s see what you do. Let’s see if everybody can find themselves at the pitch level here. Okay, here’s (sings)

That line has a whole story to tell all by itself. And you feel the quality of drama. That’s evolved over the course of how many measures (counts 1 to 11) measures, you’ve got a full story which is told by this small piece of music, this is what I love about this music. And as you get toward the end of it, I’ve written up the word drama above the last three bars, because that’s where the high point of this material is where it reveals itself. And these chorales often do that that the last few measures have the full power of the conclusion of his story. Let’s sing the tenor line now. (sings tenor line)

If you want to have an operatic aria just listen to the last thing in my voice. (sings)

It’s a very satisfying thing to do to be able to sing that and to have it come in your voice. Sing bass line. Women, I don’t trust you’re going to get down there, so sing it an octave higher.

And, men, here we go. (sings bass line)

Okay, pick a part. How many basses do we have? How many of you want to sing bass? Okay, tenor. Tenors? Altos? Okay, sopranos? Anybody up there? Okay. All right, she can anybody can reach soprano, then fine. Let’s sing as a choir. Okay, here we go. (David, class sings)

Okay, I want to speak now (on) the start of variation technique. Variation process, I think, is at the heart of composing. To be able to take whatever material you have, and to be able to see it in various ways. So, from the very beginning of this piece, simply look at the opening phrase. (plays phrase on piano) The second mini phrase here is essentially repetition of that. (plays phrase on piano)

But listen now, first phrase sounds like this. (plays piano)

The same soprano line is now supported this way. (plays piano)

Okay, look at the next phrase coming up. (plays piano)

And you’re gonna see that same phrase at the end of the line, the last measure plus now sounds like this. (plays piano) Sorry.

And that’s repeated one more time with variation. (plays piano)

Change of key. So from the very beginning of the piece, you have a phrase sounding like this. (plays piano)

And it’s done.

And then the second time (plays piano)

And then a third time, but in a different pitch level. (plays piano and sings)

So the first time it happens. (plays piano)

The next time it happens is coming up, just further down that line a little bit. Hang on, the music is running away here. And then at the very end of the line, we’ll do that one.

And one more time. (plays piano)

Okay, now look at the heart of the piece, the middle of it. Let’s sing from the opening and then we’ll get to where I want you to go. So sing soprano. (sings, plays piano)

Now look at this passage coming up and sing it and hear it and feel it. (sings, plays piano)

That passage happens again to end the piece. So look at the last three measures plus the pickup. (sings, plays piano)

And how quite different that the composer has made it. So in the course of a very short piece, it is simply packed with idea. Able to take simple material, and create independent lines because all of these now – this is not harmonization – this is line-making. This is melody-making at its highest order. And out of that, within that, the capacity for variation and the need for variation as he’s done it.

So this is a primary lesson I didn’t think I was giving myself a lesson when I first started doing this stuff. But this has been a primary teaching for me.

Now I’d like you to turn your page over. And I wanted you to see these are very recent renderings of these from the just this last week, the 19th of the month, the 21st of the month that I’ve just done these small, new versions of the same piece.

So what I’d like you to do when you leave here, take these pages and go through them carefully yourself. And you’re going to see that this first measure, let’s look at the first measure of my version here. Now let’s see if I can get this going properly.

Same melody. (plays piano)

Sounds very familiar. But now you have one more variation of that tiny little thing. Look at the next two bars. (plays piano)

Keep going. (plays piano)

Keep going through. (plays piano)

And then immediately a variation of that (plays piano)

And on. (plays piano)

You’ll excuse my playing.

Okay, let’s look at number two. Now I’m going to ask you to sing and let’s start by singing alto line of number two. You already know the soprano. But let’s see if we can find ourselves in the alto line here. (sings, plays piano)

The tiniest variation – look at the alto line in the first version of this thing.

Go to number two and sing alto line. (sings, plays piano)

Radical, radical difference by change of the notes into the pure minor, right? And so this is not by any rule, it’s by my ear that says, “I like this.” So, composing is about that – it’s not by rules – it’s, “I like this. It moves me. It touches me. I want this to be.”

Okay. And let’s start the alto line and we’ll continue all right. (sings, plays piano)

Keep going. (sings, plays piano)

Sing bass line now. (sings, plays piano)

Okay, it’s it’s fun. It’s super fun for me and satisfying and I love it.

I want you to see now the piece of music which has its basis in chorale making. How many people here on the wind ensemble? So, a couple. So that you you know this piece.

This is a peace for wind ensemble called Angel of Mercy, and it was composed last year for the St. Olaf College band. And they did wonderful, wonderful performances of it on their tour and back in Minnesota. The title of the piece, and this is a concert piece, it doesn’t have any other indication of what “angel of mercy” might mean. The only reason that I can say that that title happened is that it occurred to me as I was writing this piece that that was an appropriate title for this.

I won’t say too much more about it, I want you to begin to hear what this is. And to see some of it. The opening of it is a Bach chorale. That is my own version of it. And I want to show you what has happened here.

You’re going to see if I can, I’ll just quickly sketch an idea. It’s for three bassoons. And band pieces don’t usually start with bassoon solos of any kind. But the top most voice that is the sole voice, tt starts here with the chorale. The second voice has the actual chorale melody, which is here. And so the chorale melody, the thing you primarily be listening to is in the second bassoon here. And the thing you are listening to is the newly made melody that has grown out of that chorale melody. There is now a third bassoon as a contrabassoon part. And then a double bass opens this.

And so what the chorale melodies do for me is (I use them in pieces of music) is that they open up into arias. And so we have here an aria for bassoon with the other voices as the supporting elements in it. Matthew, we set up to do that? Okay, I have a score and who would like to follow that? Maybe you can find a way to come forward and see and stand, okay.

If it’s going to be a complication that’s going to be in more than we want to do at the moment. So for those who can see and otherwise you simply listen, okay? And this is going to be the very opening of the Angel of Mercy.

And now it’s already running here but whatever. What have I missed? (recording plays)

Listen ahead now. Out of that comes another music. (Angel of Mercy continues)

Breathless, breathless music (applause)

What I wanted to simply say about that is that that music exists because of the chorale. That the chorale is kind of a door opening into the universe, if you want to think of it that way, and it pulls something through that wants to be spoken through that music, through that impetus of the chorale. And I can’t stop that and I’m kind of helpless in the face of that music. I have to. Once it starts, it pulls me and I have to keep finding it until it simply feels right. It won’t leave me alone until it’s until it’s done, until it does that.

Okay. All right, we’ve done a fair amount. What time do we have now? How much? 20 minutes? Good. Okay. Do you have any questions at this point? From what you’ve heard or what we said, so far? Anything that’s on your mind?

And it’s okay – if you. Yes?

Student

When you’re writing pieces for large ensemble, like this piece, do you write directly to the whole score?

David Maslanka

No, no, always sketching. It’ll start with things that you can’t read, no one else can read but me. It’s just pieces and bits and pieces of stuff. But I do a lot of sketching. And it’s all by hand, I don’t use a computer for my composing. Computers have their real uses. And Matthew is an expert, he understands. This is my son, Matthew, if you haven’t met him, and he is he has founded and runs Maslanka Press, and is in the process of documenting a lot of things for the sake of the of the music now.

And my composing is entirely pencil and paper. I grew up before there were computers, so I was an adult person and a full composer before computers ever happened. And I never made the switch. I much prefer being able to have just myself and a piano and a piece of paper. And when I’m doing scoring to be sitting at a desk, quietly, hearing the sounds in my head.

And if you are a composer, do not use the playback. Okay, this is a hard thing, you get addicted to that thing, like the playback is going to help you hear your music. It doesn’t. What it does is to tell you that what you have written is wrong because that playback does not sound like the music that you’re imagining in your head, it simply does not. And the dissonance that happens when you hear that and sort of accept that this is what you have composed. There is a dissonance between that and what is really going on in your soul and in your mind. And the two create a clash, which results in depression.

Yeah, all right, I’ve seen this again and again and again and again. So my thought for you as as young composers. Yes, you can use the computer to make your scores and to make parts, but start with a pencil and paper, and that exclusively. Do not use the playback. It actually damages your capacity over time to hear orchestration. Orchestration is the thing which opens up in your mind of its own self. So all these sounds open in my mind.

And I now have had the training and then the practice over years and years and years of hearing what that is and then having the vocabulary to do this.

So your job as composers is to get things on paper, and then as quickly as possible to get them in front of performers. And then you hear that. So if you write a first band piece, Dr. Thomas will I’m sure read it for you. And that’s where your training is. You have huge information that’s going to come back to you from your first effort and trying to do such things.

Okay, I want to go in a very different direction now and show you some other music, and this is music for saxophone quartet.

This piece – first when I show you the score. This presentation from Maslanka Press has was produced entirely by Matthew, he’s a master at the various forms of computer notation. And he’s, you’ve invented the typeface that you’ve used for this, is that correct? So he’s made his own typeface, which he, through his own study, has decided and understood is for the greatest clarity of reading. And it’s a very handy and beautiful thing to do.

This piece called Songs for the Coming Day was composed for the Masato Kumoi Saxophone Quartet in Tokyo. They have done a lot of my music in the past and this was the most recent collaboration that we have. It is a set of nine pieces, running about 45 minutes of music for saxophone quartet.

And the element that I want you to hear in this music. Two elements. First is the fact that these are wonderful players. And knowing as a composer that these are wonderful players, I’ve taken them to their extreme – their capacity to be extreme. And that extreme generally is quiet and slow, as opposed to fast and vigorous. So most of these pieces really require an absolute control of the instrument.

And the ability to listen to the sound that’s being made. And this is where I’ve come to as a composer, is that each sound is an entire universe of itself. Each sound.

And this is a thought I want you to explore a little bit, I want you to hear the first piece in this set. And I won’t explain too much about it. But the Songs for the Coming Day, I have this idea that we are in the process of destroying our planet, which I can say very casually like that and drop it, boom, we are doing that. And we’re going to pay a very serious price for it, we are in the process of paying a serious price, and we’re not going to escape the rest of it, the whole earth, and our relationship to it is going to change, is changing, and will be radically different in your lifetime. I have the good grace of that I’m old, and I’m going to be dead before all this happens, right? But you are going to go through enormous turmoil on this planet. And the coming time, the coming relationship of the human race to the planet is going to be radically different than it is now.

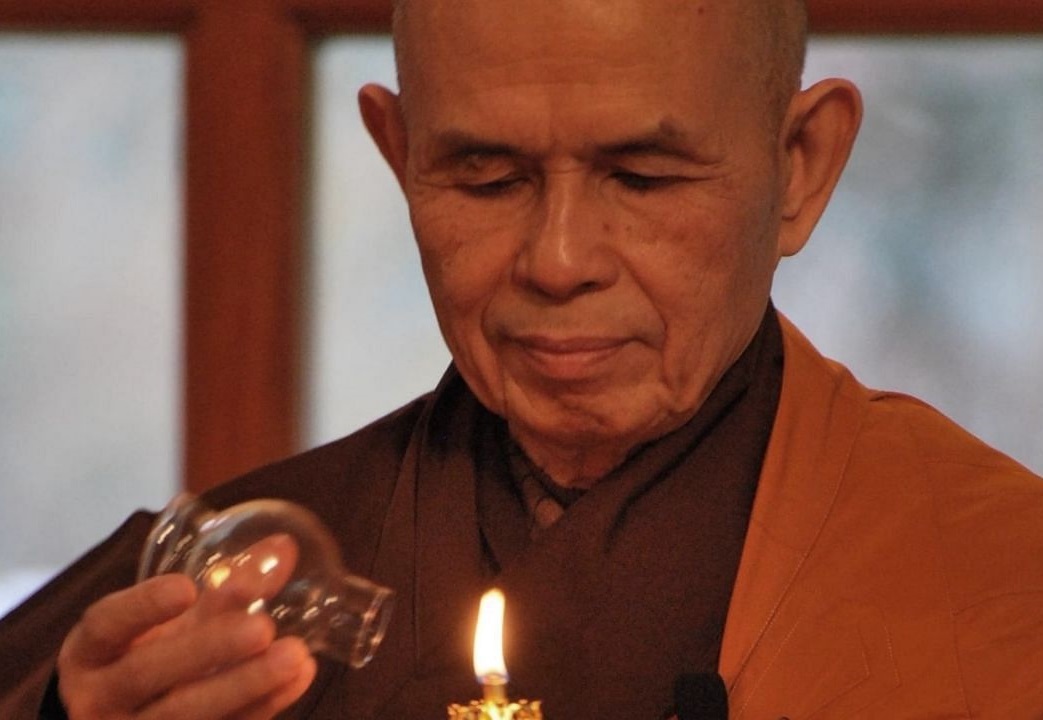

This is just my understanding, my feeling for it, and I have no no way to say other than that this is how I perceive it. And that these songs, this movement into this other place has to do with the capacity for each individual to be fully in attention to each moment that you live. It’s not about working for the future. It is being present right here right now with the sounds that you are making. And so I want to offer you that and to let you hear some of this with the idea that of the quality of focus that it takes to be present in this music.

So again, a score. Let’s put it over on this end of things this time, and let the other folks see. Is that how you want to do? Whatever you want to do. I don’t care. Yeah. And let’s find our place yeah. Okay. (recording begins)

Volume control is where?

Let’s move to… (applause)

Thank you

I’m looking for “For the dead.” Okay. I want to play one more of these for you and this one is I think number. Oh, how much time do we have?

I’d like you to hear this one. It’s called “Breathing.” It’s on two pages of music, it runs 33 measures. You’ll hear what the breathing is all about here. (recording plays)

I’m just knocked out every time by that playing. It’s just extraordinary, the capacity to play that well, to have all four voices in that saxophone quartet be equal. A string quartet, you can actually begin to see that. A saxophone quartet there’s this huge division between soprano, alto and tenor, bari. And often tenor, bari, you just don’t want to hear it. But these guys have figured out how to play these instruments.

I want to give you one more movement here. And this is going to be the fourth one in the set, it’s called “For the Dead.” It’s one of my favorite pieces out of this. This music reminds me of Shostakovich who’s one of my all-time favorite composers. One of the things that he said in his book that was purportedly an autobiography is that he wishes that every piece that he wrote could be a tombstone for someone who had been wrongfully killed in wartime. He’d been through so much of it in his life. So he wanted that quality of memorial in his music and this this is a piece of that sort.

Okay, so, “For the Dead.” (recording plays)

Okay, I wanted to (interrupted by applause)

I wanted to say a couple of things and then we’ll be finished. One is that in this music you hear all of those ideas that we talked about in the Bach chorales. That is the simplicity of melody, simplicity of material, and continual variation process, from the simplest melodic variations through shaping how the recapitulation works with the beginning – its similarities, its differences, and so on.

Okay, having said that, nobody cares about your technique. I just add that as the last thought.

So, we often as composers get preoccupied with the intellectual idea of what we think music ought to be. And nobody cares. What they want is the music. What the people who you’re writing for want is your heart. However, you need your technique. You have to develop a full capacity in your technical ability to write your music. That’s for you. But then, knowing that, you open your heart, and you let that come forward through that sound. Yeah. And that’s what I can leave you with that idea.

So well, are there any questions or thoughts? Any ideas or questions?

Student

How do you make a decision like that and not risk attacks on your (inaudible)?

David Maslanka

Oh, gosh, yeah, you know, this is the hard part, we all want to be protected. So the usual posture is like (protects body), and then there’s an open hearted one. I think the way that I can say this is that composers are by nature interior people. You live a lot of your lives inside, not only in your mind, but in your heart. And when that life shows itself, and for me, when I was in my 20s, it showed itself in a bursting way, because I didn’t know what I was doing. You know, I had the capacity, the technical capacity. But the music pushed its way out of me, and I had to follow along. This is why I discovered that I had to follow along with music, as opposed to “I’m making this up.” And in that process, a thing would appear that I didn’t know anything about except that it came, it happened, it was there. And so that’s been the way in which my music has emerged over the years is that it shows me what it wants to be. And my task has been to follow it.

The opening of the heart is, it starts with that thing, which bursts out of your heart and you can’t control it. And then over time you learn who you are, you begin to understand your own mind and what its workings are, what its troubles are, what its limitations are, what its difficulties are. And when you begin to clarify those things, then you have the capacity simply to be. You have the capacity to be.

And then in that capacity, this has the possibility of opening up. And then it’s trust. There’s a trust that it’s going to be received. Yeah.

Yeah. Occasionally, and I don’t read reviews. Occasionally, people say silly and stupid things, and you can hurt. Yeah, sure, you can get hurt by people not liking what you do. But I tried to simply protect myself from that, and don’t go there.

So best I can do to let it happen and then to come with invitation by your gracious invitation to come and see this brought forward and see the community here as best we can.

So we talked yesterday about the idea of courage as a composer. The courage is your capacity to keep coming back to your work regardless of how you feel. So I want to say the last thing I’ll say, I guess the whole question will start happening now. The composing is not about how you personally feel on a given day. Yeah? Because your moods are going to be variable. You can feel awful on a given morning. “I don’t feel like composing, I’m not going to do that,” you go and do something else. Your task as a composer is to say, “I feel like crap, I’m going to go write music.” It doesn’t matter because what wants to come out is not about what you’re feeling at that moment. It is about what it wants to be. And then your mind then organizes itself toward that. And then you begin to move with that until it finds its completion.

So a piece which takes say, two or three months to finish, your moods are (gestures). And the piece goes (different gestures) like that.

And that’s your job is to be able to follow that. And so if you take nothing else from this little bit of a lecture, take the three words – just show up. If you do, something can happen. If you don’t, nothing can happen.

So that’s how that goes. Well, thank you for your attention. You’re very kind. (applause)

And if you have opportunity, come in and listen to the rehearsals and recording sessions for…as young composers, you need to be there, right? Find a way to come in and hear what we’re doing. And just be there, okay.