In May 2003, Tiffany Woods emailed David a series of questions in the course of writing a paper. She was a student at the University of North Carolina Greensboro and taking a Band Literature course with Dr. John Locke. David wrote a thorough response. The interview has been excerpted from their correspondence and interleaved here. It has been lightly edited for spelling and style.

Tiffany Woods: I’ve read your interview with saxophonist Russell Peterson and first I want to talk a little about your compositional process and you referred to what you termed “active imagining.” While to some degree this makes sense in terms of a ‘programmatic’ piece, such as A Child’s Garden of Dreams and maybe even the Mass, when you sit down to “compose a symphony” does the same concept still apply?

David Maslanka: “Active Imagining” is a term used by the psychologist Carl Jung. It is a way of moving the conscious mind into the space of the unconscious. They closest thing to it that most people do is daydreaming. The difference is in being aware that it is happening, and in finding ways to deepen the experience. The result is that it is possible to approach the unconscious directly and to ask for the direction or energy that wants to become music. The process applies equally to all kinds of music. It isn’t about whether the music has a story, but about opening the channel to the energy that wants to be expressed in terms of musical sound.

TW: Each of your symphonies contain elements of the Mass, and you mentioned in the program notes that each of the previous works, you saw as sort of a stepping stone. Was it a conscious decision to quote some of the same rhythms in the Mass?

DM: The music of the Mass was an outgrowth of my composing at the time, so it shared in the musical language of my previous works. It didn’t consciously set out to quote from myself.

TW: The Mass is such a large undertaking for a collective group of ensembles. And it seems as if you labored over it much like the great orchestral composers, like Brahms, who continually avoided writing his first symphony. Was the twenty year delay only for you to “feel ready?”

DM: It took 20 years to start the Mass because I knew that I wasn’t ready. I didn’t know enough about the Mass or myself or humans in relation to the Mass. It took years of living and thinking experience before it became apparent that it was time to start. Brahms may have felt something similar in feeling unready to write a symphony because of the huge work of Beethoven behind him. He was intimidated, but his particular genius finally came forward.

TW: Writing most of your music for wind band, you’ve stated it as being very difficult, in terms of the clashing colors and what you referred to with Russell Peterson as the “overtone buzz.” How do you decide which instruments to use in eliminating the “noise factor,” especially in a piece as large as the Mass?

DM: The “overtone buzz” or what I now call “band noise” is a result of the large collection of dissimilar instruments in the band. The larger the band the more nearly impossible it is to really get it to be in tune. Part of my solution has been to write for smaller wind ensembles, and to write a lot for chamber combinations within the selected ensembles. The Mass contains quite a lot of small ensemble writing. The other part of the solution is the internal hearing of sound. Once I hear a sound in my head – regardless of the size of the scoring – I feel confident that it can be made in real terms. The need is to be able to tease apart a sound I hear so that I know what instruments to use in what register and what dynamic to make it work. There is a talent for this, but also it is the result of years and years of trying stuff out and hearing how it works.

TW: The score for A Child’s Garden of Dreams, includes one of your drawings. Is the man with the bagpipe symbolic?

A Child’s Garden of Dreams original cover art. Drawing by Stephen Maslanka (1979, text likely added 1981)

DM: The drawing in the score of A Child’s Garden was done by my son Stephen when he was seven years old (he is now 30.) He brought it home from school one day and I thought immediately that the bagpiper was a magical figure blowing the world into existence. There are old Australian Aborigine stories of creation that are very much like this.

TW: During and after the composition of A Child’s Garden of Dreams, you stated that your compositional process had changed. How so?

DM: The change in my composing was the discovery of “active imagining.” Before I realized that this was something I could initiate I was dependent on inspiration striking in a random fashion. When I began working with the dreams that inspired A Child’s Garden, I discovered that I could consciously move in the direction of inspiration. Inspiration, and the energy that drives it, are still mysteries, and they seem to hit more completely in some pieces more than others, but this way of approaching the mysteries has proven to be especially useful over the years. Active imagining has also been useful in helping to penetrate to the root of personal issues as well.

TW: Since you’re now working almost exclusively by commission, and a substantial number of those are by consortium, it’s a given that you have to take into account the members of the consortium, but do you also have their audience in mind? Or is it solely between the composer and the group?

You describe your music as coming from a “a soul need.” When a group/individual commissions you to write a piece for them, how do you know what the “collective soul needs?” Doesn’t the consortium format present an obstacle?

DM: With consortiums my focus is on the person and group that initiated the commission. That is the primary energy spot because they are the ones who initially thought it was useful to ask for a piece. When I compose I do visualize an audience, and myself as a listener. My dramatic sense is guided by hearing the music from this audience standpoint. The people who ask for a piece to be written are the beginning of the creative process. They are the first to perceive a need. Their creativity is in being able to perceive this need, and in knowing how they can create the space for the new musical energy by moving the people and resources available to them. BUT they will never be fully aware of why they wanted the music. It is my job to become aware of the energy that wants to come through. I can perceive a lot about the music but it most often takes quite a while after the music is done and has been performed for me to have a more complete understanding of its purpose. In my reading of things, the composer is a channel for an energy that wants to come forward, but that doesn’t mean that the composer has anywhere near an absolute conscious understanding of that energy. Good music continues to be valuable to listeners precisely because it it embodies a powerful mystery that is finally unexplainable. That is, the explanations are many, but they never wear out the source.

TW: A Child’s Garden of Dreams was your first “big hit” in the band world, and since then you have produced other works for wind ensemble on a regular basis. Do you have any upcoming projects that you would like to write?

DM: I particularly enjoy writing symphonies and concertos, and hope to live long enough to write a bunch more. But my primary work as a composer is to be available to hear internally what wants to happen at every new instant for the music I am writing. I have seen major changes in myself and in my writing over the years (now 42 years of composing) and am truly interested to see where this takes me.

TW: The Fourth Symphony, having played it with the UNCG Wind Ensemble, is a beast. AND TONS OF FUN! What strikes me as most interesting is the combination of the hymns, mixed meters, and constant loud playing demanded of the ensemble. Why the extremes?

DM: Fourth Symphony: well it isn’t constant loud playing, but there are certainly big moments, and the last third of the piece is pretty much unstoppable. The extreme passages are a response to an internal pressure that I experience as I open to the sound that wants to happen. These extreme moments are not my conscious decision; they are the result of allowing the musical force its full appearance. It is possible to be afraid of such experience, and many younger composers will cut off such extremes before they have a chance to fully happen.

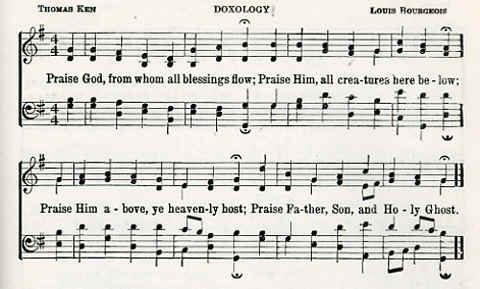

TW: The process of composing strikes me as being deeply personal. A lot of your music, in fact all of the ones that I’m discussing in my paper deal with the theme of loss, grief and transformation. And many times you use a Bach Chorale or a hymn for expression. How do you decide which chorales to use?

DM: The chorales come to hand as needed. I am a firm believer in what Jung calls “synchronicity.” That is, the coming together of things or forces that want to be together at a certain point. It can also be seen as meaningful coincidence. I don’t think that there is anything really random in the universe. Mathematicians and physicists have been wrangling with the problem of randomness for a long time. There is a lot that seems random in the universe, but I believe that consciousness is the primary organizing feature of the universe, as it is for bringing all the seemingly diverse elements of a musical composition into powerful alignment.

TW: Your Fifth Symphony, like the other works I’m discussing in my paper, is centered around the theme of transformation. You state in the program notes however that it is filled with bright and hopeful energy (much like the fourth), is there a reason these two works seem to me to be so different (in terms of mood )from the others?

DM: Concerning the moods of the Fourth and Fifth Symphonies, I don’t know if I can give you adequate reasons for the differences. The best thing I can suggest – if your analysis and thought need to take you in this direction – is that you set out to describe those moods and those differences as clearly as possible. Simple description may begin to reveal reason and meaning.

TW: All of your works are personal, and require the full energy of everyone involved in the performance and rehearsal, why the difficulties?

DM: I never set out to write difficult music, but difficulty is an inevitable consequence of opening more or less completely to musical force. That difficulty isn’t necessarily in finger technique, although musical force can push to the burning point. I can now look at pages of my music that contain “difficult whole notes.” The quality of expression that is required by any piece of music is particular to that piece, and is very exacting. Therein lies the difficulty, whatever the note values and tempos.

TW: They also seem to have a consistent, as well as persistent, rhythmic energy in them; repeated rhythms. The music is constantly moving, is this intended to be a reference to your personality?

DM: The persistent energy movement in my music is again not a conscious intent. If it says anything about my personality it is about a dogged persistence in finding the energy line through a given piece of music. Something in me won’t rest or give up until the necessary line is found. When a piece of music “makes sense” or seems to go by really quickly – even if it is a long piece – then the energy line is intact. No down time or boring moments.

TW: Dr. Locke commented in class a week or so ago that in the last fifty years music for band has really taken off. And that it is much easier as a ‘band composer’ to have works become instant hits and the demand for them to be frequently performed. Do you feel that this is due to a lack of “staples of the literature” or is it because wind ensemble musicians seem to accept new music more quickly?

DM: Wind literature has indeed taken off in the last fifty years. When I was in the Oberlin wind ensemble in the early 60’s there were just a handful of older works and a few modern works of any size. The culture for wind music has become new music, and the commissioning of new pieces. There are now a lot of very good composers writing for winds, and there is a sizeable body of good literature. The culture of wind band music used to be devoted to marches and transcriptions of old orchestral works. Now it is about new music. Students in bands and wind ensembles now grow up with a major exposure to new sounds, and grow to become part of the process of producing yet more new work. This is a very good place for wind bands to be. There may come a time when the wind band literature will have as many classics as orchestral literature, at which point it may become difficult for new composers to get their works played – as is the problem with orchestras today. But we don’t have to worry about this for a while!

TW: On a different note, I’m planning to perform your Sonata for Horn in the near future and I’m curious as to your inspiration for the work.

DM: The Horn Sonata was commissioned by William Scharnberg, and the piece grew out of the energy that I found related to him. The second movement has a personal point of reference. It was sparked by an experience my daughter [Kathryn Maslanka] had while canoeing on a lake here in Montana. She was 11 years old at the time [1996] and this was her first canoe trip. She came back all excited because they had paddled through a patch of water lilies. She said “We were among the lilies!” And that image set off the musical flow in my head.