This is a portion of the liner notes for David Maslanka: Works For Wind Ensemble, his final CD. The disc will be released on January 8, 2021.

Sacred Spaces

By Matthew Maslanka

Dr Reed Thomas makes a mean paella. For as seriously as he takes it, I suppose he should, but it was still a revelation to eat. The secret, I’m told, is in the heat and timing. He had a simply enormous pan that cooked over a charcoal pit, low and slow. Adding the rice and stock up front, he gradually added the other elements – shrimp, saffron and asparagus, among a host of other delicious treats – at exactly the right intervals. After pulling the pan off the fire, while the paella cooled enough for us to eat, we gathered for some pictures — and then we dug in. The socarrat, the lovely toasty caramelised Valencia rice at the bottom of the pan, was delightfully crunchy, flavoured with not only the seafood stock, but also every one of the layers of goodness on top.

Dr Thomas also runs a hidden gem of a band programme an hour outside of Nashville, Tennessee. Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro punches well above its weight; the ensembles there show remarkable training and professionalism.

I started publishing the music of my father, David Maslanka, in 2012. I’m the guy who prepares the music for printing, gets it printed, distributed and sold; and manages the licensing. I also accompanied Dad around the world as he visited and worked with people who were playing his music. I travelled with him to Tennessee to sort out any issues that might arise and to document the trip.

Dad and I sat down to that delicious paella at Reed’s home in late October 2016, and we all talked over the week to come. Dad would run a couple of master-classes and work with Reed and his Graduate Assistants as they rehearsed the repertoire for this recording.

My father was a quiet man. He enjoyed a lively one-to-one conversation, but he often excused himself early from parties and gatherings. He had a sharp and quick wit, but if you weren’t paying attention, the jokes would slide right by you. You’d never have guessed the shrieking, shocking, relentless music that lived inside such an unassuming figure.

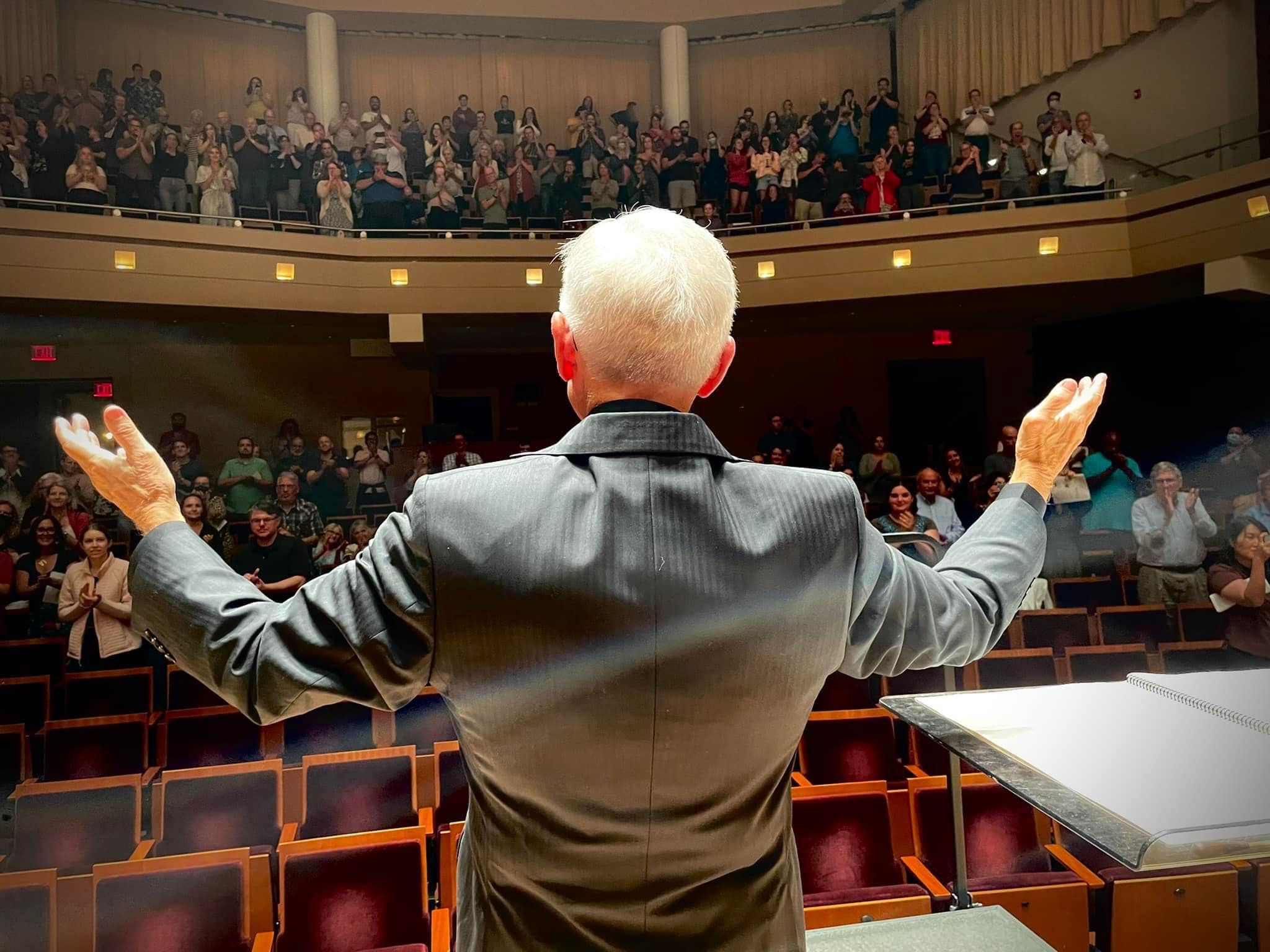

If you were lucky enough to work with him, you’d see an amazing transformation. He’d become alive and insistent, warm and encouraging, and often brutally frank. Whereas most guest artists enjoy a performance boost from the ensembles they’re there to coach simply by showing up, Dad’s presence was a very special thing. He had a gift for creating spaces where people could listen deeply to themselves, to the music they were creating and to the people they were performing with.

He combined that gift with a bone-deep understanding of every aspect of the music he had written and the instruments he had asked to play it. His priority was to help people find its true ‘heart centre’, the essential nature of the work. For him, rhythm and tone quality were the core of music, and everything else refined those elements.

Dad’s music often asks performers to play at physical extremes: so soft that the note barely speaks; so loud that the tone struggles to cohere. So slow that breath nearly gives out; so fast that it’s nearly impossible to get all the notes. He also asks for mental and emotional extremes: hold the silence until the last vibrations die out; live honestly in a full expression of sorrow.

In rehearsals, he created environments where people could find their own ways to these severe places. The extremes, he held, are where true presence and mindfulness are not only available but required. He asked people to be fully aware of themselves, their colleagues and the music. And that awareness became extraordinary performance, the ineffable connection between not only the people on stage, but with everyone in the room.

I think of a sacred space as one which has been made, deliberately, to enable some mindful activity – it has a boundary, a threshold and the promise of magic inside. We have been fascinated with such things for as long as we’ve been human, and we have worked hard at perfecting the recipe which enables transcendence in these places. Beautiful buildings and ancient rituals create spaces where we can connect with the sacredness within us.

Concert halls have some of this quality, of course. The pipe organ replaces the crucifix; we applaud when the conductor enters. Less obvious sacred spaces, though, abound. Opening your home to guests and preparing a beautiful paella for them. Stepping outside for a walk. Starting a rehearsal. All that is required is a moment of awareness that you are about to do something. That awareness transforms the experience from mundane to sacred.

During the first rehearsal of Saint Francis, the Middle Tennessee State University Wind Ensemble had been working diligently for about an hour-and-a-half, and attentions were starting to wander. They had rehearsed the second movement and were moving on to the first. The conductor, Graduate Teaching Assistant Manuel Monge-Mata, started the opening. After a couple of minutes, Dad stopped them and said:

The very first thing I want to ask you is that you must have the full attention of the ensemble before you actually give a downbeat. What happened the first time is that there’s still noise, and people still settling in. And you give a downbeat, and it surprises everybody to have that happen. Then suddenly, all the tension is there. But if the attention is immediately here – I’d like to try something with you. Have everybody please just take a deep breath and let it out. So we are in together – and let it go. All right. And now I simply want you to listen to this room space. Just listen.

Within that few seconds, you heard a few things, one of which was the person making a noise out there, which is fine. But you then paid attention to it. Right? You were fully conscious of that, as opposed to ‘well, that could happen’, you know. A truck could drive by and you wouldn’t be aware of it if you weren’t paying attention to it. But now you’re paying attention. What else do you hear in this room space? We’ll try it again. So let’s take that deep breath again. Just let it go. And then listen to your room space.

Okay – It is a remarkably quiet room. What do you hear? Okay, something is in the lights. Anything else? There’s a small air thing way down low. Anybody else hear anything? Okay, voices. Yeah. All right, suddenly you become aware. That’s all I’m trying to say: you become aware of the space in which you are sitting now. And I want you to bring this same quality of attention to the very first sounds of the piece that you’re going to play. And with that idea and to take the deep breath. Allow yourself to go deeply as opposed to ‘I gotta get through this’. Different.

[To the conductor] ‘I’m managing, I’m managing, I’m getting these people to play.’ No, they will play. You are the presence through whom they are playing. Let them have their full capacity to play as opposed to ‘I’m going to make you play’.

Okay, try that and see.

They waited for the room to fall silent. Manuel breathed and raised his baton. The ensemble breathed and prepared to play. The baton came down and the fist of God exploded from the stage.

After a couple of minutes, Dad stopped them again.

First off, you heard that first sound that was made, it was shocking. You heard it now completely, because you were ready to receive it and pay conscious attention to it. It was shocking. It was ‘oh my god’, it’s one of those.

He had invited the whole group to sanctify the space through their silence and attention. In that moment, the hall transformed from mundane to sacred. In that place, it became possible for the blood in the sound to come out and connect with the shrieking cries and delicate textures.

Throughout our time in Tennessee and everywhere we went, Dad made those spaces through his mindful presence. He then invited people to join him there. Dr Thomas demonstrated that same generosity of spirit. While it would have been natural for him to direct all of the works on the recording himself, he instead allowed each of his Graduate Teaching Assistants to participate in the music. Rubén Gómez directed Alex and the Phantom Band; Allen Kennedy prepared Angel of Mercy; Manuel Monge-Mata conducted the first movement of Saint Francis, and Martin Gaines the second movement. Reed himself directed California. The result is that every one of these conductors-in-training got the full experience of preparing a score, rehearsing the group, working with the composer and going through the recording process.

Teaching is about creating spaces where students can come to a fuller awareness of themselves and the subject. Hospitality, too, is about creating spaces where people can more freely be themselves. Music-making, fundamentally, is about creating spaces where performers and audiences can share in true connection and communion. This recording is a shadow of those spaces, as all recordings are, yet it may still serve to create a space of its own for you.

My father died in August 2017, a little less than a year after our time in Tennessee; this was the last recording project he was directly involved with.

I asked him, once, why he didn’t actively seek out the best professional or military wind ensembles to make pristine studio recordings of his music. He replied that while surface perfection is nice, it often comes at the cost of the underlying truth of the music.

Studio recording sessions are often made with every musician having a click-track in headphones. They record fairly short chunks, constantly stopping and starting. Percussion and solo instruments are often recorded in isolation booths, sometimes on different days. All of the elements are then put together in the editing process, like pieces of a puzzle. The results can be deeply impressive, technically speaking. Every note is just- so: the mixing engineer can selectively adjust individual harmonic resonance, pitch and attack/release envelopes.

Dad was completely uninterested in the kind of smooth, safe quality that process creates. His ideal was that of a heightened live performance from committed people working at the edge of their capacity. His recording philosophy was that groups should do three runs of the piece and then pick the best one. Maybe do a little patching here and there. This approach, he believed, preserves the power of the music and the through- lines of its energy. Performers can hear and respond to themselves and one another, allowing the music to breathe through them.

California ends with a piano playing a single note as softly as possible. Dad was in the hall during the recording session. On the first take, the MTSU Wind Ensemble played the entire piece from beginning to end. Reed held the silence long after the vibrations of the last note had evaporated, cradling the energy of the experience. He sustained the energy for such a long time that he grew nervous.

Later, Reed said:

I released the energy, and slowly turned around to see him standing there with a look of utter joy and a tear falling down his cheek. He simply and quietly said, ‘I don’t know how it could be better’. [It was] one of the most important and memorable events in my life.

(That’s the take they used.)

This style of recording makes the engineer’s job much harder, of course, possibilities for adjustments and fixes are much reduced. You’ll hear some imperfections in this recording. But more than anything else, you’ll hear people absolutely committed to the music and playing their hearts out.

I’m proud of the MTSU Wind Ensemble and their several conductors: Martin Gaines, Rubén Gómez, Allen Kennedy, Manuel Monge-Mata, and especially Dr Reed Thomas. Reed took the same care and mindful attention with this project that he brought to lighting the charcoal, oiling his paella pan and preparing the rice, seafood and vegetables. He had the vision. He worked with us to select music, prepared the way for Dad’s visit, orchestrated an efficient and effective week of rehearsals, and then produced this recording. I’m grateful to have been a part of it and to have worked with such excellent people.