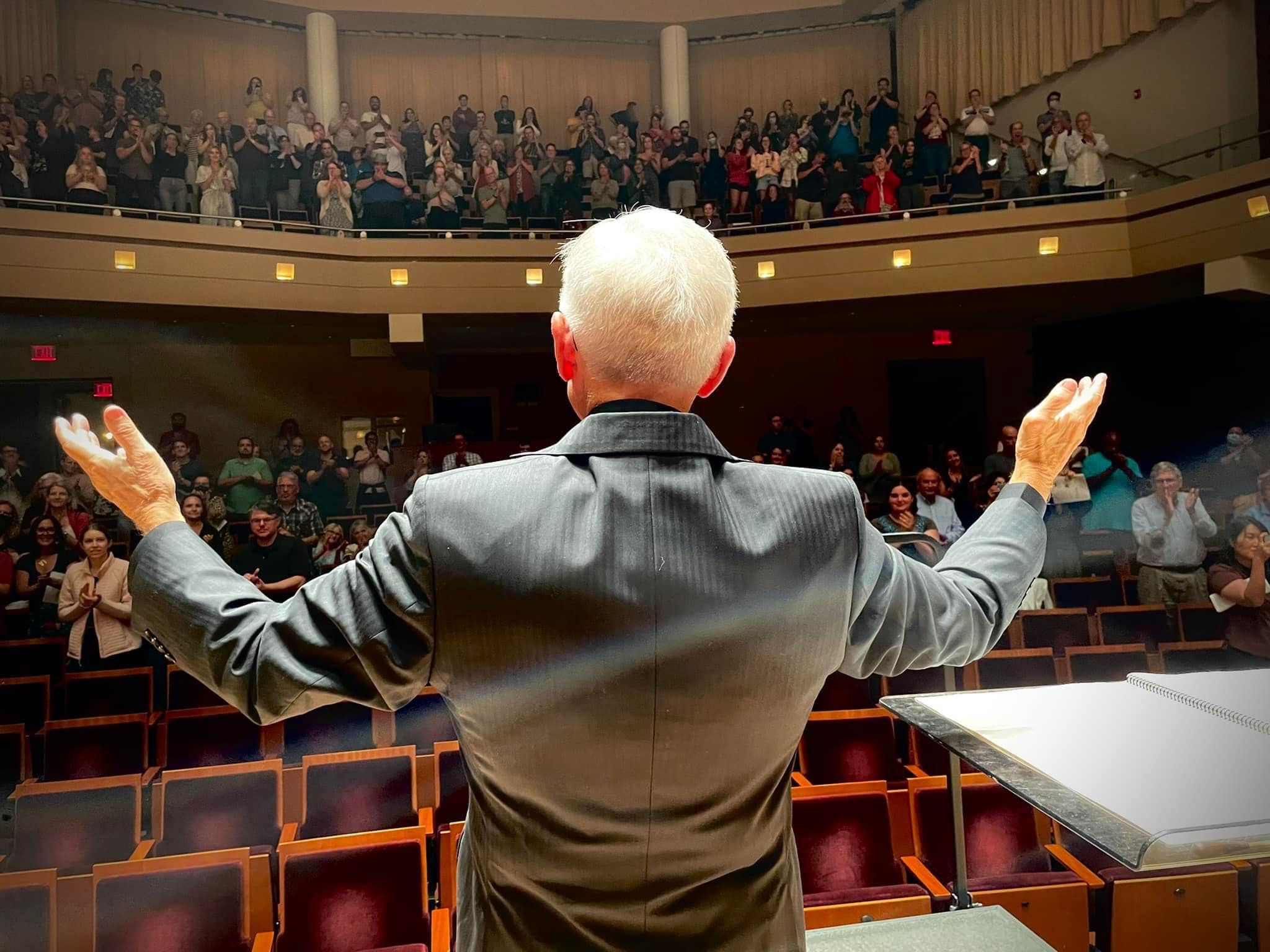

These thoughts come from David Maslanka’s forthcoming memoir, It is Solved by Walking and were written about May of 2017. I (Matthew Maslanka) asked him to write his thoughts about pivotal works in his life and then to explore the ideas that came to mind as he wrote. He filled about 100 pages in a notebook over the course of the last year or so of his life. This is an invaluable resource that we will be making available in the coming months. This section seemed important to share, especially as we are premiering his 10th symphony on April 3, 2018.

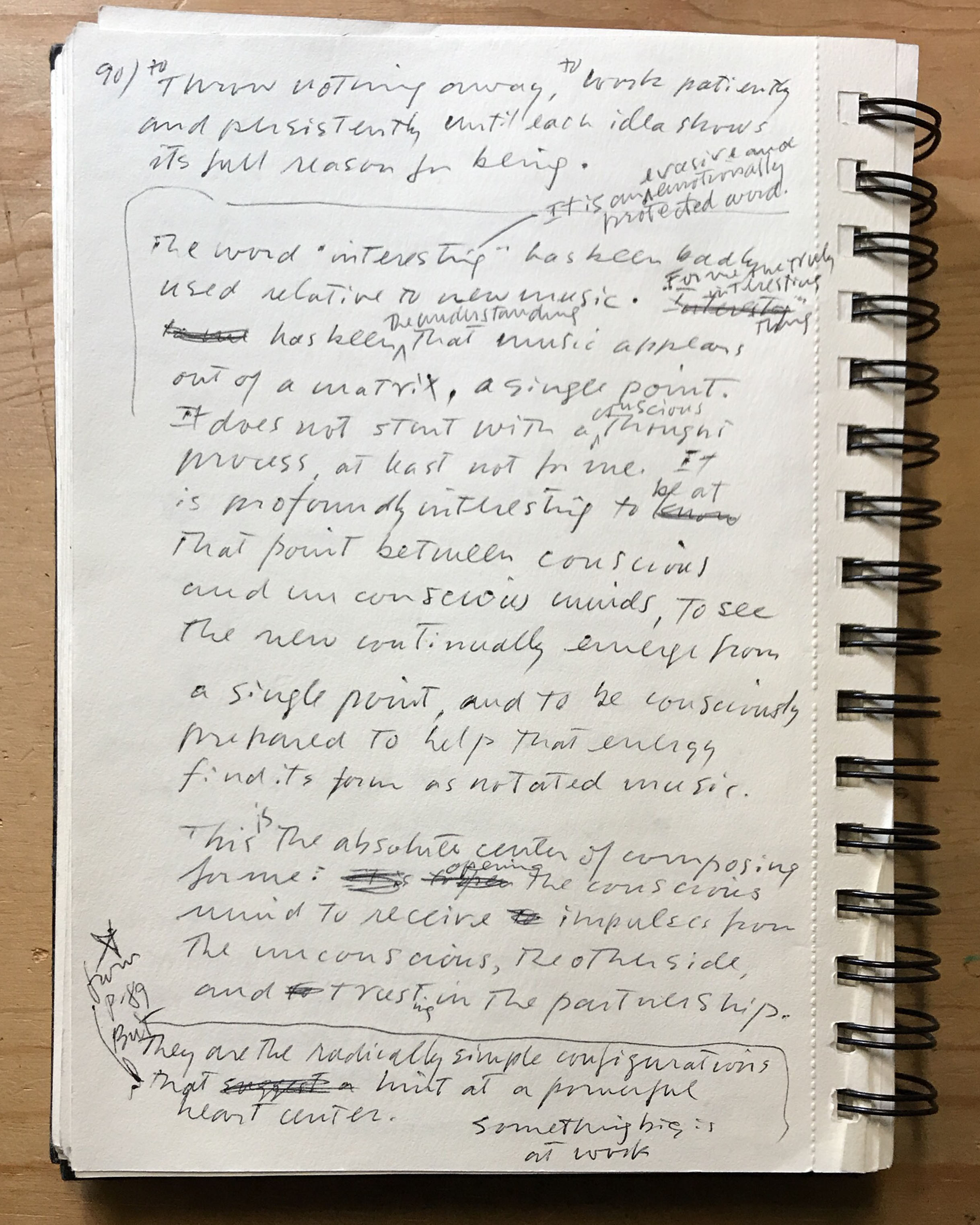

The original notebook pages are displayed at the end of this post.

This is my practice and experience as I understand it. Walking has been extremely important in my concentration practice. Walking engages the whole body, and both halves of the brain. It is an integral part of my composing process.

David Maslanka walks at Blue Mountain, Missoula, Montana. Photo by Matthew Maslanka

When the mind is relatively clear and open it is possible simply to enjoy the mental vacation. In fact, I recommend this to people as a way of recharging the mind during the course of a busy day. Walking may not always be possible but five minutes of this practice sitting in your desk lets you bring a different energy and clarity to each engagement.

When the mind is open it is possible to ask a question or make a request such as, “show me something I need to know about the person who asked me to compose;” or, “show me something I need to know about the music I am starting to write.”

I have been asked more than a few times if my practice is lucid dreaming. As I understand it, lucid dreaming is the capacity to control or direct the movement of a sleep dream. My work with inner travel and dreaming is not like this. It is not controlling but allowing.

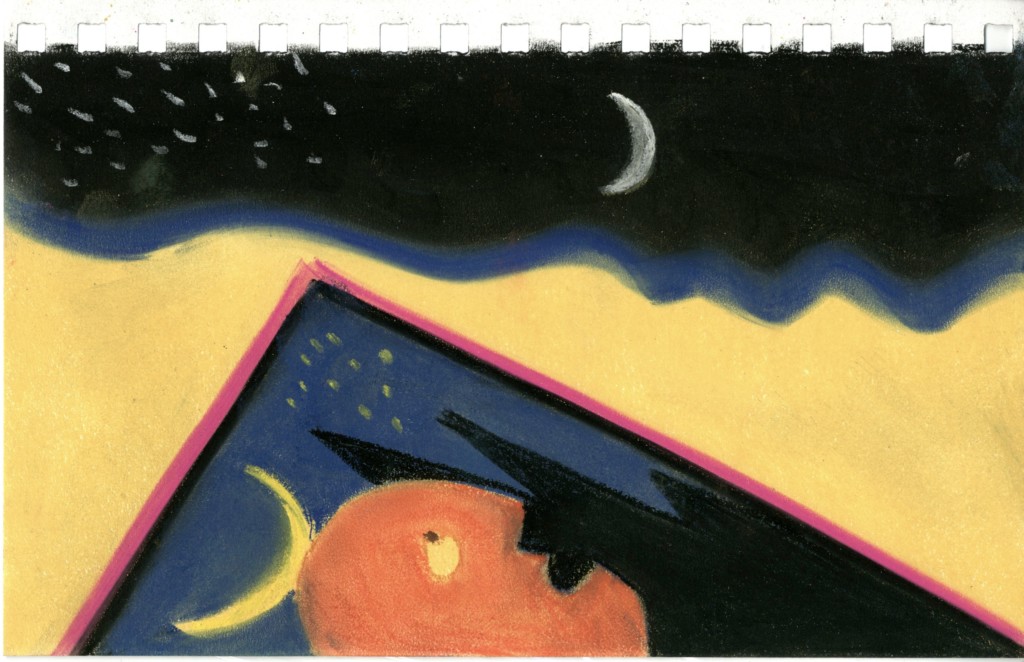

Opening to the Cosmos. Pastel on paper by David Maslanka.

It is being fully present with an inner experience – a feeling, thought, musical idea, meditation image, dream memory, etc. – allowing, following, accepting but not controlling or judging. This is not loss of control but rather partnership. The heart of music appears on its own terms and in its own time. There is what I think I want the music to do and there is what the music wants to do. The heart cannot be commanded, cannot be arrived at purely by intellectual choice. This is not passive waiting for inspiration; quite the contrary. The work is regular and purposeful.

With these ideas in mind I want to describe some of the process of Symphony No. 10. With each symphony comes an increasing sense of weight, that each has to be “important,” has to somehow match up to the history of symphonies. These are personal, emotional ideas, and not the least bit helpful in the writing of a new piece. This kind of thinking arose first with Symphony No. 5. “No. 5” has been a marking point of consequence for composers of the past. It took significant work to release the “oh my God” and worry elements, and then to let my own work become itself. Symphony No. 9 was worse. This is the serious bugaboo point for people writing symphonies in the western music tradition. “No. 9s” are historically the crowning achievement, and then … death. My No. 9 was written in 2011 and I did not die. Getting past all the history of ninth symphonies was a lot worse problem than for No. 5. No. 10 was freer in a way – not the same load of historical baggage – but the need to be “important” was just as intense. The work began as always with meditation: “show me something I need to know about the piece I am going to write.” Here is the first image that came:

The Holy Mother takes me sliding down a rocky mountain slope, all loose small rocks. It’s a wild stony country, very little vegetation, many beautiful colors in large rock formations, brilliant sun. We find a large pool nestled among tall vertical rock faces. The water is turquoise blue. We go into the pool and swim/flow downward, rising again toward a circle of light. At the surface is a “divine” place of craggy multicolored rock faces. A voice speaks my name and says, “you are ready, receive what wants to come through…We are here. You go and do.”

And the second from a few days later:

I am met by the Holy Mother in the guise of an 18-year-old Swiss farm girl – blond, pretty, traditional dress. I am shown various views of the earth and the oceans. The earth is clean, the oceans are clean. Humans have come into balance with the earth and are happy. The farm girl shows me a farm full of milk cows. The world is still technological but we are living an agrarian life, I am shown a large beautiful auditorium where music is being made. The girl thanks me for what I have done to make this new world possible. This is an odd thought for me to accept.

Then came the usual problem of composing. “I” desired to write an important piece. In my vague imagination it was like one of the big symphonies of Dimitri Shostakovich, my favorite modern symphonist. But my inner compass kept dragging me away from that, and pulling back to the humble world of the chorales. A pattern began to emerge of a chorale and a response, the response being the evolution of a radically simple, intimate, and beautiful melody. This process kept repeating itself until half a dozen of these melodic pairings began to emerge – all simple, beautiful, personal, not “important”. At each step I continually questioned whether this was the symphony that needed to be: “Really? Seriously? This is what you want me to do?” – yes. Finding the structural line for the whole piece was extremely difficult. At a certain point, I sensed that a large movement wanted to happen, but it existed only as a hard little node that had begun to rise to consciousness.

There are times in composing when the music feels like it doesn’t want to give itself up. I can sense the potential power of the ideas but there is serious resistance to finding the full expression. This happens when an idea is particularly powerful. A wrestling match is required. I have often thought that one of my best qualities as a composer is simple persistence. I am willing to do the wrestling match, however long and demanding, until the music is right.

Ideas come in different ways and with different qualities, depending on the stage of the composition. First ideas are often extremely simple, a few pitches and a few simple rhythms. I have called these “dumb” ideas because on the surface they seem absolutely banal. And yet, at the outset of a new pieces, these are the ideas that have shown up. They come with a sense of energy and urgency. They are the first hints, the root points of bigger structures that are forming deeper in the mind. There is a temptation to throw these ideas away because they are embarrassingly simple; they are not complex or “interesting,” but they are the radically simple configurations that hint at a powerful heart center. Something big is at work.

Sometimes music unfolds quickly and easily from these ideas, but as often as not I have to come back to them repeatedly until the potential they hold flowers into something powerful. This persistent revisiting is what I describe as the wrestling match. The process can be intensely frustrating. In the course of nearly every piece I will say to my wife “I am going to burn this and get a real job.” I am fascinated with the power of the utterly simple. There is a simple core quality at the heart of every good composition. The lesson over time for me has been to receive whatever ideas come, to throw nothing away, to write patiently and persistently until each idea shows its full reason for being.

The word “interesting” has been badly used relative to new music. It is an evasive and emotionally protected word. For me the truly interesting thing has been the understanding that music appears out of a matrix, a single point. It does not start with a conscious thought process, at least not for me. It is profoundly interesting to be at that point between conscious and unconscious minds, to see the new continually emerge from a single point and to be consciously prepared to help that energy find its form as notated music.

This is the absolute center of composing for me: opening the conscious mind to receive impulses from the unconscious, the other side, and trusting in the partnership.

Here are the notebook pages that were the source of this essay.