This is a guest post from Sam Ormson, director of bands at Mountain View High School, Vancouver, Washington. We asked him to talk about his experiences with David’s music. He shared this remarkable essay.

June 2015: 1st movement, Symphony 9. As the final piano notes decay into the silence of our auditorium, I lower my unsteady hands. I can feel my heart racing as I look slowly over to David Maslanka, who is standing at my right, just off the podium for our dress rehearsal for the performance of the complete symphony. His head bowed and eyes closed, I’m more than a bit nervous in this moment. “Are you nuts? Why did you think you could play Symphony 9? He said that this was beyond what he would ever ask anyone to do.” The persistent inner voice of my self-doubt was unrelenting. I finally stopped listening to this drone as David’s head came up and he looked at the group and said in a quiet voice stretched to the breaking point with emotion: “That was one of the most beautiful gifts I have ever received.”

My journey with David’s music began rather innocently as an undergraduate music education major listening from the audience. The Central Washington University Wind Ensemble and their conductor Larry Gookin were preparing Symphony 4 for a major performance, and I had the opportunity to hear this piece live three days in a row at the high school wind band festival hosted at the university. Although it would be many years before I came to know that piece in its full glory, I remember being taken aback by the cries coming from the clarinet section as they played on their mouthpiece and barrel, as well as the final chorale statement from the entire ensemble. It made a deep impression on me as a musician, one that resonates to this day. As the time passed, I experienced David’s music as an ensemble member performing Hell’s Gate, Morning Star and working on his Sonata for Alto Saxophone. All of this exposure left me with an appreciation of the deep-seated heart sense that I felt in his music, but I never seriously considered it as ‘school band’ music. I mean, high school kids are much different than college music majors, and asking them to play something of that difficultly level is certainly too much for them…

As I left college and began teaching, I filed the connection and passion for his music into my personal ‘someday’ file and never seriously contemplated when I might revisit it. My third year of teaching, as a high school band director in Las Vegas, I was searching for some music to perform with my band, a modest group with young musicians, and I came across Heart Songs. It was listed as a “medium” work on JW Pepper, and I thought to myself, “I love this music and I know they will love it too.” The journey to that performance was filled with energy, passion, and commitment to find our way towards the meaning in these notes. Talking about what the students thought the music was communicating no longer elicited responses like happy or sad, but hopes, dreams, and memories. It was different than the other pieces we played; it meant more to them and their performance was a bit more emphatic, a bit more passionate, and deeply personal.

Time marched on and I found myself at a new position at Mountain View High School in Vancouver, Washington. Again, the opportunity to program David’s music presented itself with Mother Earth. As we rehearsed this music, I noticed the students had a willingness to reach beyond their current limitations in the service of the ethos of the music. It wasn’t just about right notes and rhythms, instead it was about trying to communicate what the music was trying to say. This same connection didn’t exist with most of the other pieces I was performing with the ensemble. Again, Mother Earth was different in some way.

Mother Earth (2003). Mountain View High School Wind Ensemble, Samuel Ormson, cond.

Through the years we started to approach other music from Maslanka, and I programmed Give Us This Day. I knew that it was likely just out of reach of the ensemble’s current level of technical ability, but I also knew that we were bringing in Gary Green from the University of Miami to work with the band. When I connected with Gary at breakfast at the Midwest Band and Orchestra Clinic to talk about his visit later that year, I brought my scores with me of the pieces I was considering programming. He leafed through the selections nodding and making small comments about each until he came to Give Us This Day. He stopped, looked up at me slowly, and said to me, “Where did you get this?” From the tone of the question and look on his face, I was almost certain that I had done something wrong and that any answer was woefully inadequate for the gravity of the situation. It has just recently been published, so I said simply, “I ordered it.” Slowly lowering the score, he looked at me askance and said, “This is a work of incredible meaning and power.” As I cowered in my chair, wondering what I had done by thinking I could program this piece with my band, I hoped that my students would be up to the task of performing it.

During our residency visit from Gary, I asked him a question about a specific marking in the music and he said to me, “That is a great question; David would be happy to talk to you about it.” I was confused and thought to myself: “David? David who? What???” As soon as I realized he was talking about asking David Maslanka himself, I immediately dismissed the thought. Why would someone like David want to hear from a high school band director? His music is being performed by phenomenal college wind ensembles, and I had been dismissed by composers before when trying to ask questions about their music, but Gary insisted and I followed through. David’s responses to my questions were filled with thoughtful answers, insight into the music and an invitation to send a rehearsal recording for further comments. I couldn’t believe the humility, humanity, and generosity from this musical icon. He was willing to help us on our journey in every way possible. This was the beginning of many correspondences about his music – always useful, honest, heartwarming, and filled with encouragement.

Give Us This Day (2006) Mountain View High School Wind Ensemble, Samuel Ormson, cond.

In the summer of 2012, I bought a score to Traveler, a piece I has listened to many times before. Much like my experience when first approaching Give Us This Day, Testament, and last movement of A Child’s Garden of Dreams, it appeared to have technical challenges that were beyond the scope of my musicians in the band. But by now, I had learned to never underestimate what student musicians can and will accomplish with access to quality music that speaks to them on a deeply personal level. I passed this music out and after the first read I still wasn’t sure this was going to work – the opening line of the trumpets, the 32nd notes in the woodwinds, the exposed chamber music in the second half – there were many moments of trepidation for sure! I watched the ensemble literally transform over the course of working with this piece. From the flutes organizing multiple sectionals on their own, rehearsing challenging passages, and asking me to come in to check on their progress, to the solo flute and soprano saxophone investigating the use of vibrato and coming to me with ideas on why the blend at the end might better be served by straight tone from both instruments. The final product was the most intense performance I had experienced as a conductor from the band to date. The students who departed my classroom in the spring were not the same students that had shown up in the fall. Through discussions about the deeper meaning of this piece – life’s journey, watching parents and grandparents grow older, and the constant changes of life – we grew together. The final notes at the end of our last performance that year were followed by more than a few tears from everyone involved.

Traveler (2003) Mountain View High School Wind Ensemble, Samuel Ormson, cond.

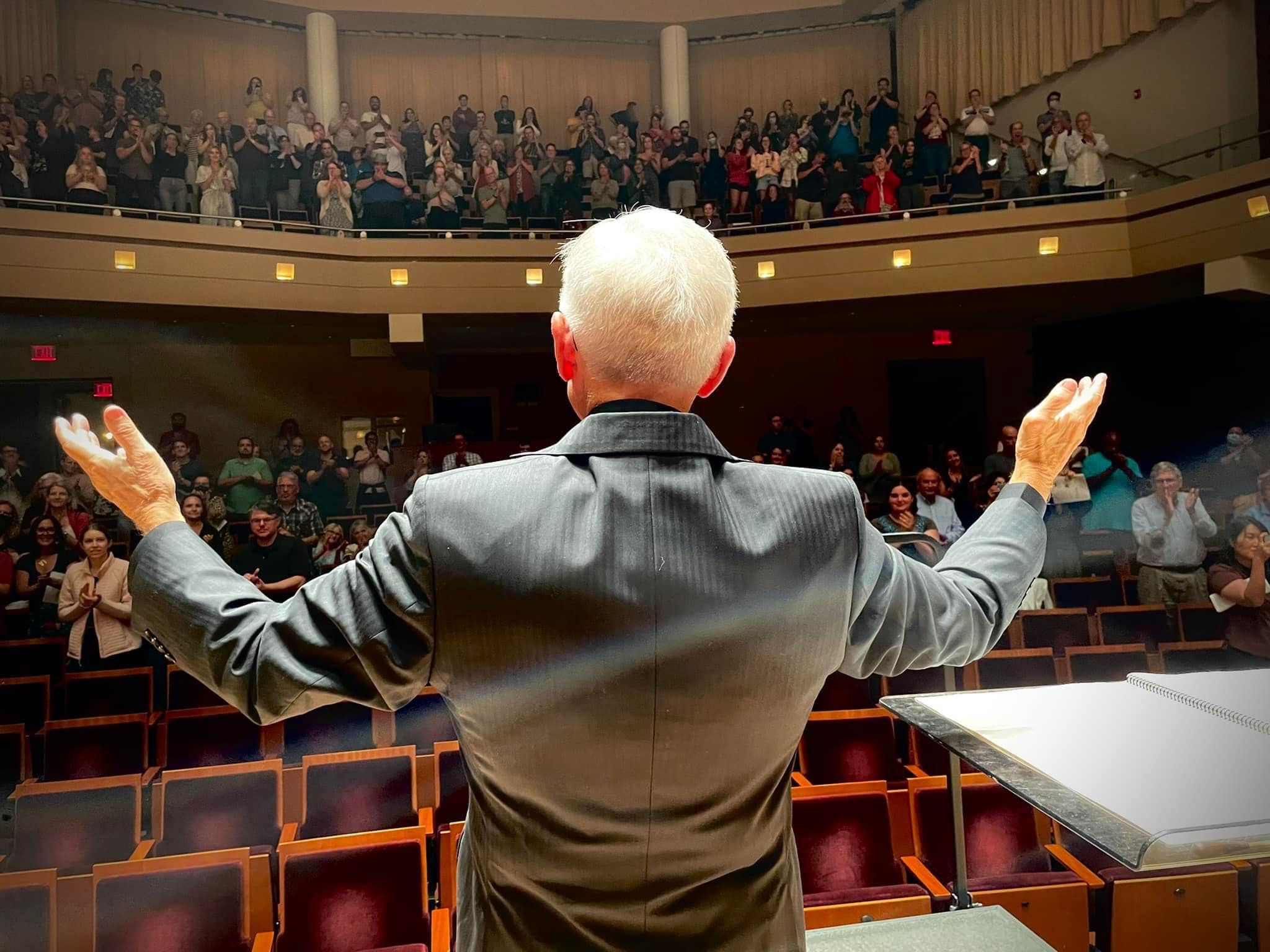

David Maslanka in rehearsal at Mountain View High School on Symphony No. 9 with Sam Ormson

In 2014, I had decided that I should push myself to perform a movement from a Symphony – David had made some suggestions and I decided that the 1st movement of the 9th was something that spoke to me and my students were completely onboard. By this time they had been the ones listening online to his music and exploring many of his other works in chamber ensembles (Mountain Roads for Saxophone Quartet, Quintet for Winds No. 1, and others). After our journey with the themes of death, forgiveness, and memory from movement 1, I began to wonder, almost jokingly at first, what might happen if we decided to approach the entire symphony. David wasn’t sure it was a good idea – asking for a 75 minute performance from a high school band at their final concert of the year, three days before the seniors graduate, might be overshooting. As I considered this, I thought back to Give Us This Day, to my trepidation about the tempo, or Traveler and my worry about the ending. I knew deep down that my students deserved the chance to experience this music, and to say something with their instruments that words can never capture. If you are wondering if an audience can sit and listen to a 75-minute Symphony, I am here to tell you that they can and that they did. It was the most attended concert I have given in my 12 years at Mountain View. That night of Tuesday, June 2, 2015 was the first and last time we played Symphony 9 in its entirety, and somehow, that is as it should be.

Symphony No. 9 (2011) Movement 1. Mountain View High School Wind Ensemble, Samuel Ormson, cond.

The MVHS high school band program has about 190 members in three ensembles. With a private lesson percentage that has never exceeded 30% of the kids in the program, Mountain View is not a conservatory school or arts magnet, but rather, a comprehensive high school band program that puts emphasis on all aspects of music making. My life as a teacher and the life of all the musicians in my groups have been forever impacted by our encounters with David’s music. Their own words are proof of that. I am forever grateful for the leap of faith that I took when I programmed his music and am reminded of the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The mind, once stretched by a new idea, never returns to its original dimensions.”