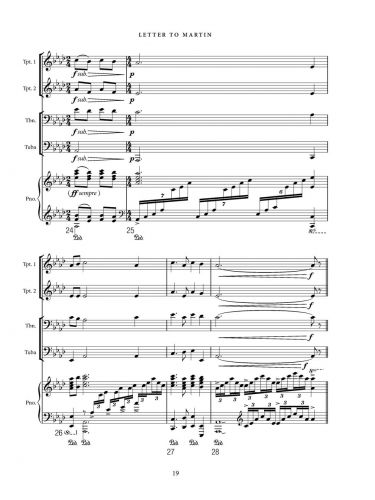

Project Description

Reader, Brass Quartet, and Piano

2015

25 min.

Listen Now

David Maslanka, reader; Andrew Jeng and Luke Spence, trumpets; Matthew Marchand, trombone; Davis Erickson, tuba; Marika Yasuda, piano

Premiere Performance for the Oberlin College Multifaith Baccalaureate Celebration Sunday 24 May, 2015 at Finney Chapel

Instrumentation

Reader Tpt-2 Tbn Tuba Piano

Commissioned by

Letter to Martin was commissioned by Betty L. Beer (OC ’65) as a gift for Oberlin College and the Class of 1965, in memory of Dr. Martin Luther King’s commencement address to our class. This composition is gratefully dedicated to Betty, our classmates of 1965, and the whole Oberlin family.

Movements

- Introductory Remarks

- Prelude

- Reader Interlude

- Amazing Grace

- Reader Interlude

- Steal Away

- Reader Interlude

- Deep River

- Reader Interlude

- There is a Balm in Gilead

- Reader Interlude

- Swing Low, Sweet Chariot

- Postlude

Program Note

Letter to Martin is a reading drawn from events in the life of Martin Luther King, and including portions from Abraham Lincoln’s farewell address to his neighbors in Springfield, and W.E.B. DuBois’ The Souls of Black Folk. I have tried through words and music to create an intimate portrait of an iconic figure.

Full Text

Dear Martin,

I am unsure how to talk to you. You are one of the greatest of the great men our country has produced. You are an American icon along with Washington and Lincoln. You are a statue, a stamp, a national holiday; thousands of streets and schools have been named after you. Like Washington and Lincoln you are venerated, and already quite a lot forgotten.

And non-violence … what happened to it? I am writing you because I wanted to say what happened to it. I wanted to talk to you like a person, like a friend. I wanted to say that you planted seeds, and what those seeds were, and how they have grown, and how they have grown in me.

Here are some stories of those seeds:

“We are gathered this evening for serious business, but before all else as American citizens, and we are determined to have the fullness of our citizenship. We are here because we love democracy, and our unshaken belief that democracy transformed from words on paper to living action is the most powerful force on earth.

“You know, my friends, there comes a time when you get tired of being trampled by the iron feet of oppression. There comes a time when you get tired of being plunged into the abyss of humiliation, where you experience the bleakness of despair. There comes a time when you get tired of being shoved out of the glittering sunlight of life’s warm summer, and left in the piercing chill of winter.

“And no, we are not wrong, not wrong in what we are trying to do. If we are wrong, then the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, then God Almighty is wrong. If we are wrong, then Jesus of Nazareth was just a utopian dreamer. We are not wrong; we are determined to fight until justice pours down like water, and righteousness runs like a mighty river.”

And the people rose to their feet with a powerful wave of applause. You realized that this speech, with scarcely any preparation, had evoked more response than any other speech or sermon that you had ever given. You came to see for the first time what the old preachers meant when they said, “Open your mouth, and God will speak for you.”

Not long after, you had settled into bed when the telephone rang. An angry voice said to you, “Listen, and listen good: we’ve taken all we want from you. Before next week you’ll be sorry you ever came to Montgomery.”

And you tell the story of your fear in words like these:

“I was shaken. All my fears hit me all at once. I had reached the edge. I got up and walked the floor but I couldn’t stop the fear. I was ready to quit. I tried to think of any way I could get out without seeming a coward. I thought about my beautiful new-born daughter and her gentle little smile. And my wife asleep in the next room. And I couldn’t stand it anymore. I was weak. I bowed my head over the kitchen table and prayed out loud: Lord, I’m trying to do the right thing, but Lord, I am weak now, I have lost my courage. I am at the end of my ability to do this. I can’t face this alone.

“And then I heard the quiet assurance of a voice inside me saying: Martin Luther, stand up for righteousness. Stand up for justice. Stand up for truth, and lo, I will be with you, even unto the end of the world.”

Then you recalled further:

“I tell you I have seen the flash of lightning, and heard the roar of thunder. I’ve felt sin overwhelming my soul. But I heard inside me the voice of Jesus telling me to keep fighting. He promised never to leave me. I felt the Divine presence as I never had before. My fears fell away. My uncertainty vanished. I could face anything now.”

September 15, 1963, church bombing, Birmingham, Alabama, in which four young girls died.

And you spoke words like these:

“Never will I forget the bitterness and grief I felt on that awful September morning. Children are God’s promise to us, and no one could tell what life could have been for those young girls. These young children – blameless, beautiful – were the victims of blind hatred, victims of one of the most heinous crimes ever committed against the spirit of life. Yet they did not die in vain. They are heroines and martyrs of a holy crusade for freedom, justice and dignity.

“So, they have something to say to each person, whether black or white, that we must choose courage over caution. They say that we must see and think past the individuals who murdered them to the system and way of life that produced these murderers. Their deaths say to us that we must work with all our hearts and without ceasing to bring the American dream into reality. No, their deaths were not in vain. God can still render good out of evil.”

The music: the Sorrow Songs, the Freedom Songs that got you through the darkest times:

W.E.B. Du Bois once wrote: “The Negro folk song – the rhythmic cry of the slave – stands today as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side of the seas. It has been neglected, despised, mistaken and misunderstood, but it remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people.

“So, in 1871 the pilgrimage of the Fisk Jubilee Singers began. North to Cincinnati they rode – four half-clothed black boys, and five girl-women – led by a man with a cause and a purpose…They went, fighting cold and starvation, shut out of hotels, and cheerfully sneered at, ever northwards. And ever the magic of their song kept thrilling hearts, until a burst of applause in the Congregational Council at Oberlin revealed them to the world.

“Then the soft melody and might cadence of Negro song fluttered and thundered.”

And Martin, you went on to say that “with this music, a rich inheritance from our forbears who had the endurance and the strength of heart to find beauty in song, whose unlettered minds were able to create the profoundly simple statements of faith and hope, we can also give voice to the depths of our pain and our yearnings. Through music the Negro is able to transform the depths of suffering into a sparkling and fluid optimism. In this dark world he somehow finds the light.”

And non-violence….

You said that world peace by non-violent means is neither absurd nor unreachable. All other ways have failed. Thus we must begin again.

How long will it take? The rich power of your voice, the cadence of your speech ring today in our hearts and minds:

How long? Not so long, because lies cannot live forever.

How long? Not so long, because the universe bends toward justice.

How long? Not so long, because mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord, trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored … His truth is marching on.

Lincoln’s words on leaving Springfield for Washington in 1861 could have been your words. He said, “What great principle or ideal is it that has kept this Union so long together? I believe it was that sentiment in the Declaration of Independence which gave liberty to the people of this country, and hope to all the world. This sentiment was the fulfillment of an ancient dream … that [men] might one day shake off their chains and find freedom in the brotherhood of life. We gained democracy, and now there is the question whether it is fit to survive.

“Perhaps we have come to the dreadful day of awakening, and the dream is ended. If so, I am afraid it must be ended forever. I cannot believe ever again that men will have the opportunity we have had. Perhaps we should admit that, and concede that our ideals of liberty and equality are decadent and doomed….

“And yet – let us believe it is not true! Let us live to prove that we can cultivate the natural world that is about us, and the intellectual and moral world that is within us, so that we may secure an individual, political, and social prosperity, whose course shall be forward, and which, while the earth endures, shall not pass away.

“I commend you to the care of the Almighty, as I hope that you in your prayers will remember me … Goodbye my friends and neighbors.”

Then a little more than a century later, in February of 1968, just two months before your own passing, you spoke out thoughts like these in a Sunday sermon:

“Once in a while I think about my own death and my own funeral, not in a morbid way, but I ask, What would I want someone to say?

“If any of you are here when it is my time to meet my end, don’t make it a long funeral. And if someone gives the eulogy, ask them not to make it too long. And every once in a while I wonder what I might ask them to say. Ask them not to mention the Nobel Peace Prize – that’s not important. Ask them not to mention all the other awards, or where I went to school. Those things are not important.

“On that day I’d like someone to mention that Martin Luther King, Jr. tried to give his life in the service of others. On that day I’d like someone to say I tried to love somebody, say that day that I tried to feed the hungry, and clothe the naked. I want someone to say that Martin Luther King, Jr. was a drum major, a drum major for justice, a drum major for peace; say that I tried to be a drum major for righteousness. And all those other shallow things won’t matter. I won’t have anything to leave behind – no money, none of the fine things of life. But all I want to leave behind is a committed life. And that’s all I want someone to say.”

I thank you, Martin Luther King, Jr. I thank you in the name of all of us here, the members of the class of 1965 to whom you spoke so memorably, and all of our other friends, old and new – God bless, and rest in peace.

Further Reading

Maslanka Weekly: Best of the Web – No. 31, Letter to Martin

Maslanka Weekly highlights excellent performances of David Maslanka’s music from around the web. This week, we honor the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as we remember him through David's composition, Letter to Martin.

David Maslanka: Works for Younger Wind Ensembles

Here are more than twenty works for wind ensemble, arranged in approximate ascending order of difficulty, with commentary by David Maslanka

Recording the Wind Ensemble Music of David Maslanka

Mark Morette of Mark Custom Recording shares his extensive experience in recording wind ensembles.