Maslanka Weekly highlights excellent performances of David Maslanka’s music from around the web.

From Keitaro Harada’s Website:

Conductor Keitaro Harada maintains a growing, international presence throughout North America, Asia, Mexico, and Europe. Recently named Music & Artistic Director Designate of Savannah Philharmonic, he will conduct the 2019-20 opening and closing concerts before his inaugural season in 2020-21. Harada’s broad scope of musical interest in symphonic, opera, chamber works, pops, film scores, ballet, educational, outreach, and multi-disciplinary projects leads to diverse and eclectic programs.

Keitaro Harada hosts a livestream entitled Music Today where he has the opportunity to interview conductors and musicians, often focusing on a single piece of music. This week, we feature Keitaro’s interviews of Scott Hagan and Kevin Michael Holzman on David’s Symphony No. 10 and Symphony No. 4.

Symphony No. 10: The River of Time

From Matthew Maslanka’s program note:

Symphony No. 10 was commissioned by a consortium headed by Stephen K. Steele, Scott Hagen (University of Utah), and Onsby Rose (The Ohio State University). My father passed away while writing the work. I completed the composition based on his sketches.

Dad wrote about the origins of the symphony:

The work began as always with meditation: “Show me something I need to know about the piece I am going to write.” Here is the first image that came:

The Holy Mother takes me sliding down a rocky mountain slope, all loose small rocks. It’s a wild stony country, very little vegetation, many beautiful colors in large rock formations, brilliant sun. We find a large pool nestled among tall vertical rock faces. The water is turquoise blue. We go into the pool and swim/flow downward, rising again toward a circle of light. At the surface is a “divine” place of craggy multicolored rock faces. A voice speaks my name and says, “You are ready, receive what wants to come through…We are here. You go and do.”

And the second from a few days later:

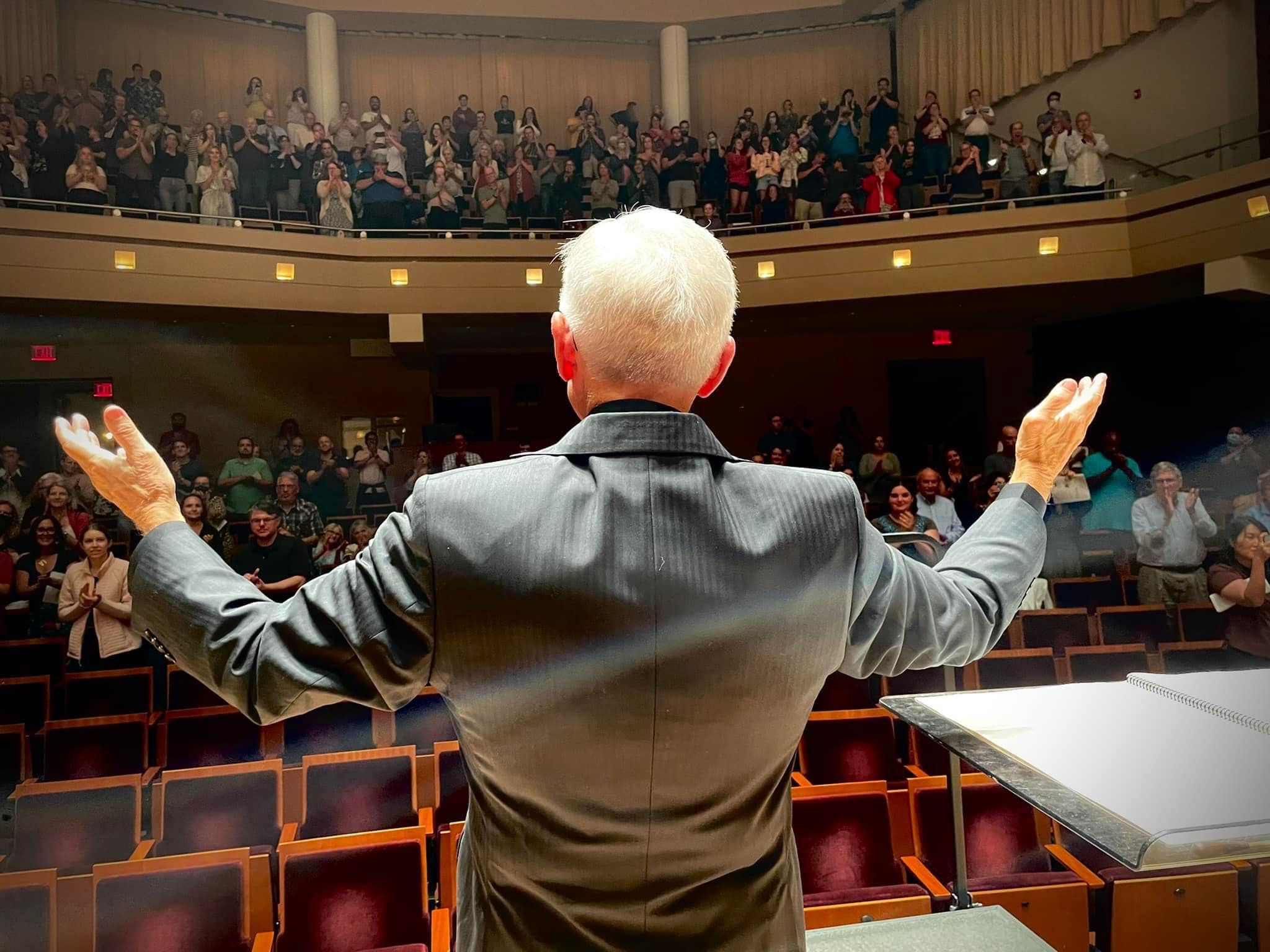

I am met by the Holy Mother in the guise of an 18-year-old Swiss farm girl – blond, pretty, traditional dress. I am shown various views of the earth and the oceans. The earth is clean, the oceans are clean. Humans have come into balance with the earth and are happy. The farm girl shows me a farm full of milk cows. The world is still technological but we are living an agrarian life, I am shown a large beautiful auditorium where music is being made. The girl thanks me for what I have done to make this new world possible. This is an odd thought for me to accept.

Then came the usual problem of composing. “I” desired to write an important piece. In my vague imagination, it was like one of the big symphonies of Dimitri Shostakovich, my favorite modern symphonist. But my inner compass kept dragging me away from that and pulling me back to the humble world of the chorales. A pattern began to emerge of a chorale and a response, the response being the evolution of a radically simple, intimate, and beautiful melody. This process kept repeating itself until half a dozen of these melodic pairings began to emerge – all simple, beautiful, personal, not “important.” At each step, I continually questioned whether this was the symphony that needed to be: “Really? Seriously? This is what you want me to do?” – yes. Finding the structural line for the whole piece was extremely difficult. At a certain point, I sensed that a large movement wanted to happen, but it existed only as a hard little node that had begun to rise to consciousness.

At the time of his death, my father had fully completed the first movement and half of the second. The remainder of the second movement and the whole of the fourth movement were sketched out. The third movement (“the hard node”) had an opening sketched, but the rest was in fragments. Dad asked me to finish the work if he were unable to complete it. I drew on my long experience working with dad and his music to first understand the sketches and then to piece them together.

Dad titled the completed first movement after his wife and my mother: “Alison.” He was writing as my mother was dying of an immune disorder in the spring of 2017. This movement may be seen through that lens, with bitter rage at the coming loss and a beautiful song full of love.

I have named the subsequent movements. The second movement’s title, “Mother and Boy Watching the River of Time,” comes from my father’s final pencil sketch of the same name. It depicts two small figures sitting on a riverbank in front of a forest and mountain foothills. The music is largely a transcription of the second movement of the euphonium sonata he wrote for me, Song Lines.

The third movement posed a special challenge. The movement was both at the emotional center of the symphony and the least finished. One tune, marked “The Song at the Heart of it All” in the sketch, became the heart of the work and of the symphony. The full statement of the theme may be found at bar 174, with a quiet restatement in the solo euphonium at bar 217. It is a pure expression of love: my love for my father, his love for me, my mother, sister, and brother, and by extension, love for humanity. The restatement of the opening material, though at first comforting, becomes jarring and unsettled, rising to a dissonant roar. The euphonium soloist is left to scream, “why?!” at a world that seems content to keep spinning.

The third movement became my response to the deaths of my mother and father. It is not what dad would have written; rather, it is a synthesis of my mind and his, colored by extraordinary pain and loss. I have named the movement after my father.

The fourth movement, “One Breath in Peace,” is the acceptance and ability to move forward after loss. The long solo lines for oboe reflect and extend the bookending chorale, “Jesu, der du meine Seele.” Dad’s customary morning practice was to play one chorale from the Bach 371 Chorales. He would sing each line as he played along on the piano. In this way, he came to deeply understand these miniature jewels of western music. I have closed the symphony with the last statement of the chorale, with the pianist singing the tenor line. I hope you will hear his voice in it.

Watch below as Keitaro Harada interviews Scott Hagan about Symphony No. 10.

More info

- Keitaro Harada

- Scott Hagan

- Symphony No. 10: The River of Time @ davidmaslanka.com

Symphony No. 4

From David’s Program Note:

The sources that give rise to a piece of music are many and deep. It is possible to describe the technical aspects of a work – its construction principles, its orchestration – but nearly impossible to write of its soul nature except through hints and suggestions.

The roots of Symphony No. 4 are many. The central driving force is the spontaneous rise of the impulse to shout for the joy of life. I feel it is the powerful voice of the earth that comes to me from my adopted western Montana, and the high plains and mountains of central Idaho. My personal experience of the voice is one of being helpless and torn open by the power of the thing that wants to be expressed – the welling-up shout that cannot be denied. I am set aquiver and am forced to shout and sing. The response in the voice of the earth is the answering shout of thanksgiving, and the shout of praise.

Out of this, the hymn tune Old Hundred, several other hymn tunes (the Bach chorales Only Trust in God to Guide You and Christ Who Makes Us Holy), and original melodies which are hymn-like in nature, form the backbone of Symphony No. 4.